Ali Smith:

She sat in a clump of grass at the side of the path in the early spring sun. The grass was wet. She didn’t care. There were bees and flies out and about. A small bee-like creature landed on the cuff of her jacket and she flicked it away with a precise flick of her thumb and first finger.

But a fraction of a second after she did she realized the impact her finger must have had on something so small.

It must have felt like being hit by the rounded front of a giant treetrunk that’s been swung through the air at you without you knowing it was coming.

It must have felt like being punched by a god.

That’s when she sensed, like something blurred and moving glimpsed through a partition whose glass is clouded, both that love was coming for her and the nothing she could do about it.

Ali Smith:

This is all in Cennini’s Handbook for Painters, as well as the strict instruction that we must always take pleasure from our work : cause love and painting both are works of skill and aim : the arrow meets the circle of its target, the straight line meets the curve or circle, 2 things meet and dimension and perspective happen : and in the making of pictures and love – both – time itself changes its shape : the hours pass without being hours, they become something else, they become their own opposite, they become timelessness, they become no time at all.

Ali Smith:

I am wondering where it is, grave of my father, wondering too where my own grave, when the boy sits up, faces the woman’s house, holds his holy votive tablet up in both hands as if to heaven, up at the level of his head like a priest raising the bread, cause this place is full of people who have eyes and choose to see nothing, who all talk into their hands as they peripatate and all carry these votives, some the size of a hand, some the size of a face or a whole head, dedicated to saints perhaps or holy folk, and they look or talk to or pray to these tablets or icons all the while by holding them next to their heads or stroking them with fingers and staring only at them, signifying they must be heavy in their despairs to be so consistently looking away from their world and so devoted to their icons.

Paul Feyerabend:

Dear reader,

In a few pages you will find a story written in a style you may be familiar with. There are facts and generalizations therefrom, there are arguments and there are lots of footnotes. In other words, you will find a (perhaps not very outstanding) example of a scholarly essay. Let me therefore warn you that it is not my intention to inform, or to establish some truth. What I want to do is to change your attitude. I want you to sense chaos where at first you noticed an orderly arrangement of well behaved things and processes. It is clear that only a trick can get me from my starting point — the footnote-heavy essay I just mentioned— to where I would like you, the reader, to arrive.

My trick is to present events which dissolve the circumstances that made them happen.

I’m currently making my slow way through a borrowed ebook on my phone — it’s a practice I’ve gotten into in the past few couple years using Libby, an app provided by a DRM content distributor that partners with many libraries, and which allows you to check out digital copies on “loan”.

The main advantage of this is I don’t have to carry any extra weight with me when I travel, which makes it convenient for reading in my commute and during unplanned moments of free time. I also don’t find the material experience of reading something on a screen, even an LCD screen, to be that uncomfortable. All the same I’m inclined to return to physical borrowing in the future, and today a couple reasons for that occurred to me:

A phone engenders something like ”context collapse” on an individual level, in that it condenses so many disparate activities and elements of a life (my web browsing, my work communications, my note-taking, my personal messages, my reading...) into a single physical unit, and not only makes moving between those contexts frictionless, but actively merges and collages them on one surface (e.g.: a slack alert pops over the top of the page while I read). It’s not a new observation, but I think this deteriorates our ability to focus and compartmentalize effectively, and I’d rather my reading not get caught up in the maelstrom.

I have this experience of slight disappointment on the subway every day, seeing (and occasionally participating in) the sea of people all absorbed in their little screens (Oliver Sacks writes on this sentiment very eloquently here). I don’t doubt that at least some of them are doing something vitally important, or something virtuous like reading, note-taking, drawing, or so on. But a phone, in my observation, puts up a kind of psychic wall between you and your surroundings: it actively clings to your attention like a magnet and blocks out your surroundings.

- If a phone is like a car (eyes on the road, hands on the wheel), a physical book feels to me like a bike: you pedal for a while, and then cruise and let the momentum propel you. I often pause after reading a paragraph, and spend a few minutes staring into space and digesting the passage (something, I might add, that I can’t conveniently do with my phone, because my screen shuts off). In this way it’s a much more passive recipient of your attention, although I grant that there are books, too, which ”suck you in”.

(not to mention ebooks are prohibitively expensive for libraries!)

Here are some hopes of mine for the editorial thesis/approach of Making-Remaking:

Underscore the artificial and contingent character of our everyday conceptual categories; the way they transform, fuse, and fall in and out of favor across different speaking contexts and time periods. My hope is this attitude becomes a tool for the reader to use in unraveling everyday metaphysical disputes, and in unlearning our contemporary physicalist dogmatism.

Uncover the mutual relationship between creation and understanding, by which I mean the following ideas:

To properly understand and grapple with a text, a work of art, a technique, etc., you have to treat your engagement with it as an activity rather than a passive receipt of information; through your interpretation of the source material, you engage in a sort of creation.

On the flip side, a recognition that all creative works are derived out of previous works and the surrounding context in which they were produced.

Something I would like to understand better is the modern allure of serendipity, and whether or not it”s justified.

Hilary Putnam introducing “thick ethical concepts”:

The word “cruel” obviously...has normative and, indeed, ethical uses. If one asks me what sort of person my child’s teacher is, and I say “He is very cruel,” I have both criticized him as a teacher and criticized him as a man. I do not have to add, “He is not a good teacher,” or “He is not a good man” I might, of course, say “When he isn’t displaying his cruelty, he is a very good teacher,” but I cannot simply, without distinguishing the respects in which or occasions on which he is a good teacher and the respects in which or the occasions on which he is very cruel, say, “He is a very cruel person and a very good teacher.” Similarly, I cannot simply say, “He is a very cruel person and a good man,” and be understood. Yet “cruel” can also be used purely descriptively, as when a historian writes that a certain monarch was exceptionally cruel, or that the cruelties of the regime provoked a number of rebellions. “Cruel” simply ignores the supposed fact/value dichotomy and cheerfully allows itself to be used sometimes for a normative purpose and sometimes as a descriptive term. (Indeed, the same is true of the term “crime.”) In the literature, such concepts are often referred to as “thick ethical concepts.”

A dream of mine is to build a sort of RSS reader specifically for NYC arts and culture event listings, and to get institutional buy-in from museum, library, and university organizers, so that there would be a common and open way of gathering this kind of information.

The current unacceptable paradigm is that everyone posts on instagram (and occasionally individual event calendars) to get the word out.

Instagram, walled garden that it is, doesn’t give developers access to search or aggregate posts, so effectively the only way for me to find happenings that may interest me is to manually go through the profiles of organizers that I follow, or sift through my non-chronological, ad-crusted feed to discover listings.

i would want to see this tool/platform exist 😭

Would LOVE this

04/06/2025

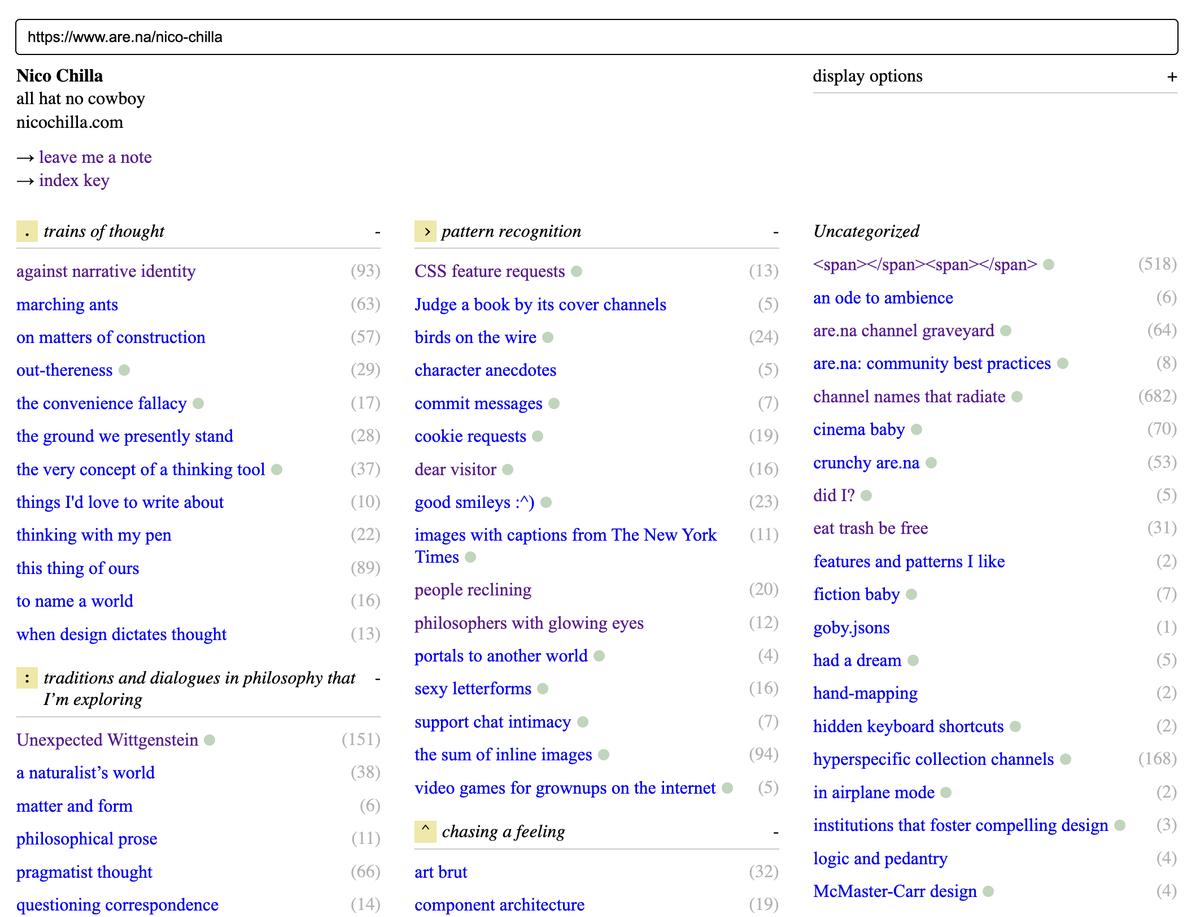

Hey Nico, I saw your index viewer— love it 🥺 SUPER HONORED to be one of the example indexes! Hope everything’s well with you ❤️

@selina-kehuan-wu haha thank you! and of course, gotta spotlight fellow power users 🤝 likewise hope all is well :)

When I’m designing, the pathway to making progress is always a lot less straightforward than developing — the latter feels like a linear progression of tasks whose complexity is simple to gauge up front, whereas the former is more of a spaghetti-throwing exercise.

Consequently I’ve been hemming and hawing for a few weeks about how much time to invest in prototyping the goby interface before starting to develop it; it can feel a bit aimless and unsatisfying until you land on a promising direction. But just in the past few days, I’ve been spending my evenings pushing myself to sketch on it, and finding truth in this remark from Hayao Miyazaki:

I must battle my desire to avoid a hassle. All important things in the world are a hassle.

I think I’ve landed on some elements of the design system and a look & feel which “click” for me, although they obviously need refining. What helped in reaching this point, beyond just sitting down to work on it for consecutive days, was a couple approaches:

A return to by-hand sketching! I think this keeps me from getting too caught up in fidelity, and it’s more comfortable/portable than working on a laptop screen. I feel like this is where many of my favorite interface concepts for goby have come from.

Note-taking: specifically, I found it helpful early on to make a list of the minimal elements I would need designed in order to make a basic implementation; it helped me stop thinking about them as individual design components, and more as an interconnected, modular system.

Focusing on functionality: In the past I’ve gotten caught up with testing different styling and type treatments, without being able to land on something satisfactory. This time I tried to start by answering questions about the logic and signaling done by the interface: e.g. how much information will I show to users at different points, how do I make the data structure clear, how can I make this kind of interaction visually consistent, etc. What I found was that this drove me to innovate on the form and find approaches which feel non-arbitrary and stylistically unified.

Natalia Ilyin:

As it turns out, the computer was “a tool,” but not the tool those 30-years-ago “early adopters” believed (because they had been told to believe) it would be. It was no pencil: It made getting into the profession expensive, and the expense of the tools had an immediate effect on who got into the business. The migration of design onto applications and then to internet applications and lease agreements cost money, and now never stops costing money. So that is the first thing. Computers made design a profession for people who had the money to join in. You needed seed money. Before computers, you could own an X-acto knife and a pen and a drawing board and make money. I know because I did.

Second, demanding that designers use computers--making InDesign the industry standard, for instance, pressed people of talent into a regulated way of working that made their work easier to commodify. The universality of the tools took designers from being unique individuals with their own unique voices and methodologies to users of a system of “creation” that was in fact a system of indoctrination and labor exploitation.

are.na index viewer:

@nico-chilla i love this! so simple but so clever :0

@rosemary yay, so happy to hear it! hope you were able to try it out with your profile :)

My eternal frustration with the intersectionObserver API is that it detects intersections based on the portion of the element being observed that is within the observer’s boundaries (configured via the threshold option). This results in a lot of cases where you’d intuitively expect the callback to fire, but it doesn’t; for example, if I have a child element that is taller than the boundary container, it won't necessarily fire a collision once it passes the top of the boundary, since the height ratio that’s in-view hasn’t meaningfully changed.

In my experience it would be far more useful in most cases if it fired entries based on the portion of the root/boundary container that is filled by observed elements. That would allow you to easily detect, for example, when an element covers less or more than 50% of the viewport (you can achieve this now, but only with a bit of non-optimal hacking).

cool website!

why thank you 👉😎👉

right?!

I found your website through Are.na, it's inspired me to pursue my own :)

wow, so happy to hear that! by the way, I like your username (or epic real name??)!

thank you :) happily, my name!

E: I need to pick clothing for tomorrow; what’s the temperature going to be like… I know it’ll be—

N: It’ll be cold!

E: But how many layers of cold?

Greta Rainbow:

Lately, I’ve been parroting the Annie Dillard line “How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives,” applying it to affirm the simple desires of the people I love. My friend wants to go on vacation. My boyfriend wants to quit Instagram. My parents want to move to an island. It’s cheesy, easily found on Etsy as a Papyrus-font poster print, and yet it’s the best I seem to have. Dillard meant it as an aphorism about choosing presence over productivity. Her ideal daily schedule was that of a turn-of-the-century Danish aristocrat who got up at four in the morning to go hunting with his friends. They converged at a babbling brook where they swam, drank schnapps and ate a sandwich, had a smoke, rested and chatted, and hunted some more—until he showered, dressed in formal wear, ate a huge dinner, smoked a cigar, and slept like a log. His wife, meanwhile, birthed and tended to their three children. This is not the writer’s life, but the writer must also contend with a schedule, must build a scaffolding of mundanity that allows the reading and writing to be done. And though each day is the same, “you remember the series afterward as a blurred and powerful pattern.”

If how we spend our days is how we spend our lives, we will spend much of life hunched over a hot MacBook.

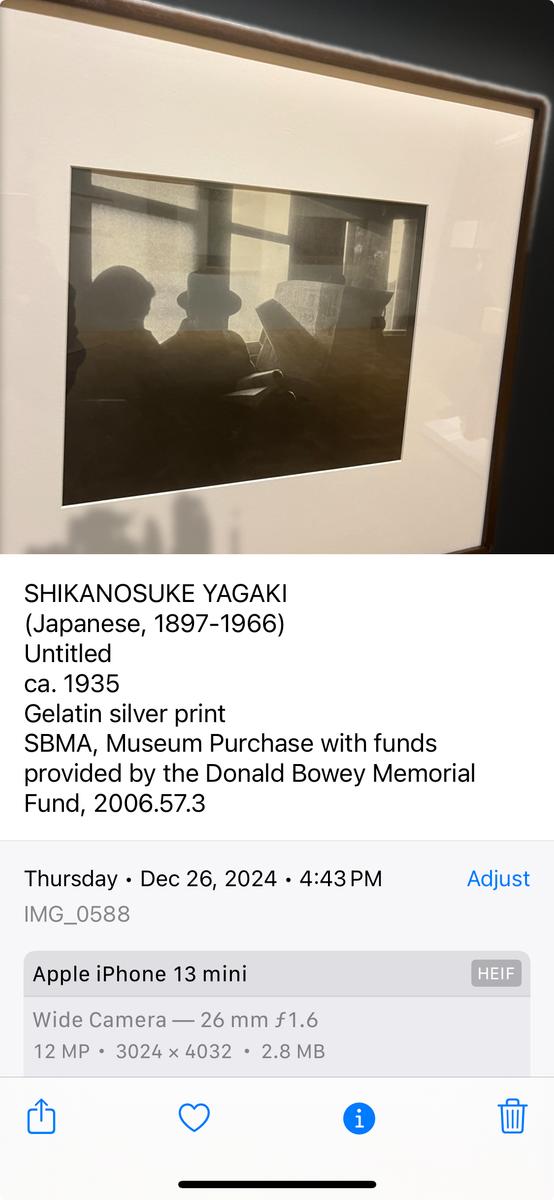

IOS photo captions and OCR:

Patrick Yang MacDonald:@nico-chilla <3 will think of how to put into words my own hopes