what do we mean by creative?:

People will often censure ChatGPT, DALL-E, and other AI products for stealing human intellectual and creative output without compensating the sources of their data. As this line of thinking goes, the works generated by these programs are purely derivative; they take advantage of human originality to generate infinite renditions that then compete with and cheapen the value of the works they were trained on.

My concern is, if you compare AI authorship and human authorship, it seems like this attitude penalizes behavior in AI which we consider harmless and ordinary in humans, not to mention foundational to human creative practice: Like generative AI, people absorb large amounts of writing and artwork corresponding to their disciplines; interfacing with that existing world of intellectual output develops our mastery of language and understanding as writers, or of craft as artists and designers. I think producing “original” work then consists not of working from a clean slate, but rather making new connections and observations, remixing, reframing, challenging existing material, intermingling it with our individual experiences. Looked at this way, human work is ‘derivative’ in the same way AI works are derivative.

You might justifiably challenge me on this: you could argue that even if people do similarly start from an existing corpus, they grow it into work which is more inventive, more rational, somehow more “original” than AI output. And aside from these doubts, I obviously grant that today’s AIs don’t have personal histories and experiences that inform their work. But the first response I have to this kind of skepticism is that it feels like philosophical hedging to me. That is: it draws a line around the state of the technology today and uses that as an essential delimiter of what AI is capable of, and of what differentiates human and AI creativity. I think this is an ill-advised position to take, not just because the technology is evolving rapidly, but because at a fundamental level I don’t believe there’s any categorical boundary barring machines from becoming as creatively competent as professional human authors.

My second response to this skepticism is that regardless of AI’s actual capabilities, I’m actually more interested in what the mere possibility of genuinely generative, creative AI means for the way we understand our own work. What if the only thing that significantly distinguished the quality of the output of a machine from that of a human was the fact that a machine can do it a lot faster, and with far vaster resources and references than any human can gather? Like a piece of good science fiction, that looming technological threat allows us to reframe our preconceptions about the world: it allows us to reflect on creativity and creative value not as essential qualities, but as concepts formed out of contingent social, economic, and human conditions.

Something I think I’ve noticed about myself is that I slip into different states of “flow” where my attention and decision-making become bound to particular patterns. For example, when I establish deep focus on a particular task or activity, I become obsessed with it — even my absent mind gravitates towards it, and it becomes difficult to think intentionally about anything beyond it. At other times I just succumb repeatedly and absent-mindedly to habits, like listening or watching something while I brush my teeth (I’ve done this for long enough that I now find it uncomfortable to brush my teeth without any auditory accompaniment).

This connects to a confucian idea I heard a while ago (ironically on a podcast, which I probably listened to while brushing my teeth): people tend to naturally fall into patterns of behavior; it’s the role of ritual to break those patterns. So although rituals can feel forced and arbitrary, they disrupt rather than maintain the status quo — I really like this framing.

My problem with the “it’s all subjective” line of thinking isn’t necessarily that it’s a position with no merit, but rather that it masks a lack of understanding, and prevents meaningful disagreement or reconciliation of different points of view.

Matters of artistic taste, matters of ethics, these things can’t be reduced to differences in personal preference, like your favorite flavor of ice cream. Again, that’s not to deny that they are relative in an important sense. But their relativity is contingent on shared culture and a shared human condition.

Something I would like to think about more intentionally is serendipity, and particularly the role of serendipity in the techno-capitalist age we live in.

A conflation I would like to explore: we typically use “narrative” to mean a chronology, but we also use it to refer to representations of people or things at single moments in time. Maybe the meaning has expanded in this way because we pull from our pasts to generate unified representations of our present selves?

People often use the term “philosophy” to describe a set of rules or guiding principles for how to behave, but I like to think of it as almost the antithesis to this: philosophy is what you do when your rules cease to make sense or fail to account for your present circumstances. This is similar to the distinction that John Dewey marks between “customary” and “reflective” morality.

some thoughts on designing collaboratively:

One thing that it has taken me a while to wrap my head around is how designers work collaboratively; design seems to depend on the execution of a single coherent vision, and I wasn't sure how you could bring multiple people into that process as equal creative partners.

In my first forays into the professional world, I've gotten exposed to several approaches to this, and I’m tentatively forming an insight about what works well for me: it’s ideal to avoid situations where multiple people independently tackle the same asset. This forces a team to try to consolidate and litigate between different concepts that each author feels creatively invested in. In my experience it’s far easier to build on a single concept, driven by one primary author, through discussion and debate with backseat collaborators.

As a primary author, I’ve really appreciated this model because it allows me to address my collaborators’ feedback in a way that feels unified and coherent with my own ideas. And on the other side, I was surprised to find that as a backseat collaborator I don’t feel creatively disempowered (although this is partially to the credit of generous collaborators). On the contrary, I feel creatively empowered because I can spitball ideas and amendments to the design without putting the primary author under any pressure to accept them directly, and the end product feels like something which I share authorship in.

I should probably make clear that this is by no means a categorical rule: there are probably many cases, such as a preliminary ideation phase or a particularly large project with many components, where working simultaneously is useful or even necessary. It just hinges on being and working with collaborators that don’t invest too heavily in their own ideas, and possibly having a hierarchy where lead designers set the direction and adjudicate disagreements.

Janna Levin & Joshua Jelly-Schapiro:

Kleptoplasty is a phenomenon so strange and alien that before its discovery it would have been considered physically and anatomically impossible. Certain sea slugs can steal an algae’s lifegiving material, sucking up DNA, proteins, and cells through a straw-like organ. The slugs are then able to photosynthesize, metabolizing light just like the planta they’ve pillaged, turning green with chlorophyll. The divide between fauna and flora, alive or not, dissolves under the pressure of this discovery. How can you not be moved? Where is the sense in insisting, “No, I am a slug. And you are a plant”? Or “I am the plant and you are the slug”?

In that dissolution is a demonstration of the cultural power of science. The seemingly obvious axioms of our humanity—who we are, what we are—are in an instant reconceived.

Contrary to Wittgenstein’s famous dictum, I’m now of the attitude that ideas do transcend language: you can believe something without being able to articulate it. But I think his basic point was that ideas don’t live in some untouchable mental realm; they manifest themselves in our everyday practices and dispositions.

I think there's something to the idea that we read not only to open our minds to new ideas, but also to find better articulations of the ideas that resonate with us, words that give form to our existing attitudes.

Foreword to The Most Beautiful Swiss Books 2023 exhibition at Pratt Institute: a conversation between Gaia Scagnetti Hwang, Chairperson of the Pratt Graduate Communications department, and Scott Vander Zee, Adjunct Assistant Professor

Gaia on bookmaking as an act of inquiry:

At the core of our MA in Communications Design at Pratt lies the foundational idea that the program serves as a space for students to learn not only to manipulate design as a mode of production but also as a mode of inquiry. This educational framework shifts away from traditional academic paradigms.

When bookmaking is approached as a mode of inquiry, rather than simply as a means of dissemination, the relationship with the production chain undergoes a significant shift. The goal of bookmaking isn’t just to produce, but to investigate, experiment, and explore. As such, each specialist involved in the design and production process becomes a collaborator in the research itself.

In light of this, a provocative question arises: If the act of bookmaking is itself a form of inquiry, how does that redefine the relationship between the graduate students and the specialists involved in the production chain? Given your expertise in the field of book design, I am keen to hear your insights on this question: Does the reframing of bookmaking as a practice of inquiry alter the stakes when graduate students engage with the entire production process?

Scott on production as R&D phases:

Bookmaking—as an art and /or craft—can only truly succeed through multiple forms of inquiry. They (books) are investigations into language and its formulation; systems, hierarchies, and dramaturgies; printing and binding techniques; and various aspects of materiality they are formal objects; sensory experiences; and capsules of physical presence, time, and thought. They are a technology, etymologically speaking. Within this framing, the best-case scenario is for students to become as much of a specialist as possible with the production processes of bookmaking and its impact on design.

The production process, despite typically being associated with mechanical finalization, actually begins (or should) at a book’s conception—inquiring into what’s relevant and appropriate, captivating, affordable, ecological, etc. From the beginning of any book project, designers undergo a series of R&D phases. The reason being, that production cannot be an afterthought in bookmaking. This is why students’ engagement with them plays such a crucial role in understanding the full spectrum of design and its processes and, within the context of a school, why it’s important to see them explore and experiment with all such possibilities.

Gaia on books without arguments:

You raise a compelling point. What intrigues me is the notion commonly held by students that research and production are separate phases, or at least distinct skill sets. This perspective seems to relegate research to an optional, purely intellectual process that operates in a vacuum and is needed mostly for innovation. On the other hand, production is often perceived as a vocational process—reliant on the dexterity of skills and developing from a concrete objective and outcome.

This false dichotomy lies at the heart of many of the failures in our discipline. It often prevents design projects from communicating through an argument or a point of view.

And to take a step forward in our conversation, I feel it’s worth exploring those failures in this context. Specifically, what types of books do we end up with when production is merely an afterthought. What do books look like when they are designed without an argument? Or, maybe even further, do books always communicate a point of view regardless of production choices? This reminds me of the 1972 edition of Learning From Las Vegas designed by Muriel Cooper versus the 1977 paperback edition. I feel that the two editions live in two parallel universes

Scott on designing with intentionality:

The types of books we end up with when the production is an afterthought and /or they are designed without an argument, is what we see 85-90% of the time. One thing I always try to get across—about design in general, but typography and typesetting specifically is that it should have an attitude. That’s not to imply it has to be an aggressive, brutal, or bold one; however, design decisions should feel intentional. Intentionality functions as the argument in design and the forethought of production.

Agreed. Most editions do live in parallel worlds-especially if redesigned. This is what makes editions interesting, regardless of which is perceived as having a higher value or better design. Kind of like re-issues of recordings in music, etc. Regardless, there’s an inherited conversation between them all. Similarly, this newspaper sets in dialog with the official catalog related to the exhibition of The Most Beautiful Swiss Books as well.

Gaia on “the magic”:

Building on our earlier discussion, it’s evident that the design process can yield unforeseen narratives identities that are sometimes unexpected even to the authors. Books are such good examples of the revealing power of design, the ability to show us more evidently what we might have intuitively perceived but now is presented in front of our eyes. This is the magic that happens at the intersection of intentionality, argument, production, and inquiry.

Nico! I just discovered that you actually have a webpage on your site made from this inbox. That's amazing. Do you physically copy paste every note, or write codes that automatically take text and apply to the site?

@nico-chilla oh wow, this is way more advanced than I thought!

Martin Scorsese on Letterboxd:

I love the idea of putting different films together into one program. I grew up seeing double features, programs in repertory houses, evenings of avant-garde films in storefront theatres. You always learn something, see something in a new light, because every movie is in conversation with every other movie. The greater the difference between the pictures, the better.

Over the years, I’ve been asked to pair my own pictures with older films by other people that have inspired them. The request has come from film festivals, which present the pairings as a program. The terms “inspiration” and “influence” aren’t completely accurate. I think of them as companion films. Sometimes the relationship is based on inspiration. Sometimes it’s the relationships between the characters. Sometimes it’s the spirit of the picture. Sometimes it’s far more mysterious than that.

“It’s a very personal kind of expressivity, a meditation on character where the music and the editing is meant to share the filmmakers’ — and they are filmmakers — readings,” said Francesca Coppa, a fandom scholar who teaches English and film studies at Muhlenberg College. “And then other people buy into those readings, like, Yes, I totally see that.”

Ms. McLaughlin says that editing helps her process what she’s consuming. “It’s kind of like when you have a thought and it isn’t fully realized until you say it out loud,” she said.

nico!!!!!!!!!! thank u

the commitments we make:

Following up on my takeaways from an interview of Masha Gessen:

I think what I find compelling about the idea of a “liberatory” framework for gender — as opposed to a “rights-based” or deterministic one — is that it moves us away from fraught metaphysical debates that never resolve, and towards conversations about the recognition we humbly ask of and depend on from one another. In other words, the rights-based framework forces our discussion of gender to be argumentative and combative, whereas the liberatory framework turns it into an open social dialogue.

And more broadly, that seems to me to be a good way of thinking about morality in general — it’s about the commitments we make to each other, not what we categorically owe each other.

going around doing my fall edition of guestbook signing! tell me about someone u love!

Hi Dani, what a wonderful tradition.

I will tell you about Frida and Diego. Unlike their namesakes, they are brother and sister, the surviving two kittens from their litter, now around one and a half years old.

Frida is a coal grey with green eyes, and Diego is silvery white with light blue eyes. When they adopted, my parents were told Diego was the confident one who liked to be in the center of the action, and Frida was very timid. This continues to perplex us all, because the reverse has been true in our experience. Frida is possibly the most affable, trusting, and loving cat I have ever met. She befriends most people within minutes of meeting, and she is quite chatty. Diego is terrified of everyone. When my partner and I visited this month, he lurked around and silently observed us, only becoming comfortable in our proximity after about a week. He is, more like my childhood cat, independent, food-driven, and endearingly moody. Among their shared joys and pastimes are:

watching the squirrels and birds in the yard playing with toys food. mischief. food-related mischief.

thank you for this sweet answer! @nico-chilla

something i have always loved is when pets' names come in pairs. i also miss living with cats so much. the stubborn part of me feels committed to ensuring diego would not be terrified of me somehow. like, my last roommate in new york had a cat called ursula and i loved her so much. she was possibly the meanest cat i've ever met but she would still keep me company and i loved feeling her presence. i was so determined to having her like me, and i think she did! but she definitely didn't respect me because of it.

maybe frida is secretly diego and diego is secretly frida. cats are such gifts. what was your childhood cat called?

ah yes, food-related mischief, the best kind.

thanks for tuning into the walkthrough on friday too :~~)

Lara Palmqvist:

In every way, the literary life involves collecting: words and ideas, libraries and anthologies, yes, even architectural dictionaries. One of the writer’s essential duties is to gather—to filter and weave fragments, to refract perspectives and form new points of contact. The reader, in turn, acts the Widsith’s listening audience, learning from the sojourner’s song how to speak of the textures of life. Such is the ongoing, collaborative nature of a language we are not born knowing; we cannot express ourselves without first encountering the words of others. As is often remarked, effective writing serves not as explanation, but invitation—a bowerbird’s nest of noticings, calling other minds to take roost.

Lara Palmqvist:

I do not equate advanced vocabulary with intelligence, though I do suspect precision is another way of becoming more present. As Hempel suggests, I believe that hoarding or heeding words—whether slang, vernacular, or verbs-turned-nouns—is a means to improve our attention and, by extension, ourselves. We can read for plot, for story, or for information, but reading for words affords unique gains; every term amassed further liberates us from falling back on default language, thus granting as much fidelity as possible to whatever we wish to express or describe.

Lara Palmqvist:

The dictionary is part of my own reading process; if I come across a word I do not know, I look it up and record (or hoard) the definition in a notebook. This can make for slow going, as when I recently read Karen Joy Fowler’s We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves, narrated by a woman with an outsize vocabulary. Yet the effort to define new words never felt tedious; rather, I felt a sense of intentional awareness similar to when a biology course taught me to identify species of birds by their songs. The noisy symbols on the page suddenly held meaning: oneiric, pertaining to dreams; verklempt, overjoyed. I’d found word-treasure, and Fowler had provided the map.

Charles Finch:

At any moment on our planet there are at most a few dozen novelists working with great power, for a broad audience, with the material of consciousness, which is what the novel is so uniquely good at handling, how it feels to be inside us, what it means, the devastations and beauties it brings. Murakami is one of them. If his book about that experience is fitful and odd, perhaps it reveals, rather than diminishes, the undomesticated radiance of his gifts. “I am not an ornithologist,” Saul Bellow once said. “I am a bird.”

Economist Tim Jackson:

Human beings are not short-term, selfish, hedonistic consumers, or at least that’s not our entirety, and we’re losing the depth of our own humanity by living inside a system that pretends we are those individuals, and that creates all the institutional arrangements to confine us in what I see as a kind if a cage. I see capitalism as a cage that confines us to an image of ourselves that I don’t personally believe in… The only people who do seem to believe in it are economists.

My dream is for consumers to move away from using many different subscription-based, web-hosted services, each with their own cloud storage feature, and shift to a model in which each person uses just one or two services like Dropbox to sync local files across multiple devices, editing them with software installed locally and purchased through one-time or update-based payments.

One wrinkle in this that I see is that online collaboration depends on a centralized server host, typically the company providing the service. So my further dream is that we find a way to decentralize server hosting and empower ordinary users to host their own servers.

Where does a fact live, if not in a true statement?

In “operational coherence” (to use Hasok Chang’s not-so-catchy term). That is, in the successful actions taken and predictions made based on knowledge of that fact.

There is a lovely parallel that I’m starting to see here between Chang and Wittgenstein: where does the meaning of a term live, per Wittgenstein? Not in a single brittle definition, but in its use.

Maybe, just as the diverse and infinite uses of a term mean you can never reach a conclusive definition, the diverse and infinite actions you can take to validate a fact mean you can never exclude it completely from doubt. This points back to Chang’s idea of truth in degrees rather than a binary.

the pastry baker and the doctor:

I’ve heard linguists say that for all its success, the lack of mechanistic interpretability in LLMs means they don’t really help us understand how language works, and to that extent it’s more of an engineering innovation than a scientific one.

But within a pragmatist conception of knowledge, where truth is grounded in applicability and direct contact with experience, how do we make sense of this? Would AI not be a model of good science? Here is maybe one way of making sense of this: AI technology can produce impressive results in the contexts that it was designed for, i.e. simulating coherent human behavior, but unlike a typical scientific model, it doesn’t provide concepts and methods that you can apply in other contexts, and connect to other domains of knowledge. The “knowledge” it provides is very brittle.

To use an old example from Socrates, it’s like comparing the pastry baker and the doctor: a good pastry baker knows how to produce things which bring people pleasure in the short-term, but they can’t relate that to things like the chemistry of the food and the functioning of the body, and they can’t predict the impact their goods will have on the health of a person in the long term. This is what doctors can do: bring knowledge from anatomy, medicine, chemistry, etcetera to bear on our everyday activities and diet, interrogating and explaining the behavior of the body.

Hasok Chang on truth by comparison:

An important distinction to make is, there’s truth by operational coherence, which works by direct confrontation with experience, and what I call truth by comparison: sometimes you say “yes, the truth of this statement consists in its agreement with other things we regard as true. So, yeah, global warming is true. Why? Because we already believe in the cogency of our temperature measurement methods, and here are the data produced by those methods.” We’re not directly checking global warming in the sense of truth by operational coherence, usually, but we’re checking it by comparison.

But now, what is truth? It’s easy to talk about truth in terms of language, of course: statements are true when they accurately describe reality. But what about reality, truth itself? The best we seem to be capable of saying is this: reality is “the way the world is” (monistic), or “the way things are” (pluralistic). Reality is “what’s true” and truth consists of “what’s real”. But what is it for crying out loud? This is the noumenal question at the bottom of it all, and I have the inkling of an intuition that the reason I have trouble answering it is that the question doesn’t make sense. It’s somehow malformed.

Here is roughly how I make sense of the correspondence theory of truth: facts are built out of basic grammatical components, each referring to features of the world. You combine them like lego bricks to create complex representations of reality. It’s the idea of a kind of isometry between representation and reality, like making a map of a territory: different symbols represent different things and their spatial relation to one another, and we assess the map’s accuracy and fidelity by comparison with the real thing, using the key and the scale.

I’ve been feeling like at least part of the correspondence theory is built into the very idea of a “representation”: a representation is a representation of something. It is not the thing itself, but it refers to it in a very special way. It says “I resemble the thing that I’m referring to, if you interpret my features in a certain way”. A challenge for anyone wanting to do away with the correspondence theory, I think, is to reconcile with the inherent notions of correspondence in the idea of representation, and in our everyday language.

As I write this, what is at least clear to me is that the correspondence theory is a theory about the relationship between truth and language. Specifically, what constitutes a fact and determines statements as factual. So it likely involves either a silent assumption about what truth is, or a definite theory about it.

Dominant user interface conventions are functionally useful for website visitors, but also a source of homogeny across the web — maybe the right mindset for a designer (in a commercial context) is that breaking them is okay, even if they cause some initial confusion for a visitor, as long as you provide cues to guide people on how to navigate a page.

tools both constrain and expand the field of possibility:

Some thoughts re: “the designer and the engineer must be able to work by drawing with a stick in the hand”:

There are ideas here I really agree with: we should strive to be independent of proprietary software, and at a basic level, I don’t think you should identify a designer’s ability with creative cloud proficiency. But I don’t think we ought to trivialize the significance of tools either.

As I’ve come to understand it, design is a field constituted by shared conventions, both internal to the designer community, in that we share common tooling and methodologies, and in public, in that we all share visual and cultural reference points. When technology and culture shift, we may pick up and discard various tools and skillsets — hot metal type exchanged for phototypesetting, etc. But this does not mean that our roles can be conceived entirely independently of our tools. Rather, the meaning of the role changes along with changes in tooling.

My perhaps divisive view is that the “embellishment, commercialization, and industrialization” of design is really all there is to design. There is no platonic design mindset or skillset outside of the contingent technologies and cultural practices which ground our work.

Some of the skills that I picked up from my own design education — e.g. the ability to articulate and justify my ideas, the ability to visually order information, the ability to research, etc — are indeed not dependent on any tool, but my role as a designer still hinges on tool proficiency and familiarity with the designed surfaces of this day and age. Typography, and the availability of typefaces, for example, are a technical skill and a tool, but also something integral to my sense of self as a graphic designer.

I can say the same of “engineering” from my background as a web developer — what I’m capable of, what I can even conceive, depends on the constraints of the html/css/js.

In design as well as engineering, I think tools both constrain and expand the field of possibility. None of what we do makes sense without including them in the picture.

I think there is something to the idea that, in order to persist in a long personal project with no outside pressure, you have to be as in love with your process as with the desired output.

Finally got around to adding a guestbook to my website! It refreshes daily from none other than this are.na channel, using the magic of eleventy fetch, the are.na api, and netlify scheduled deploys.

this is so cool

@dani-bloop aw thanks! :-)

wow, amazing solution! im inspired to experiment with this kind of set up on my homepage aswell.

@daniel-galis I see you're using eleventy as well! yeah it was surprisingly simple to set up, I managed to knock it out in a single evening

In the past I’ve debated with people about the efficacy of bullets (as designers are oft prone to do in their free time), and as a “pro-bullets” person, something I’ve just realized is that my affection for them comes from their value not as reading aides, but as writing aides. The conventions around bulleted text are such that in using them, there’s less pressure to write complete and well-constructed sentences. That makes them ideal for getting your thoughts out on the page. One might even say, “I think in bullets”.

Changing the facts can change which facts are intelligible. For example:

If Peggy is a person (fact), then it makes sense to ask “how many toes does Peggy have?” or “what is Peggy’s favorite color?”. But if Peggy is a plant (alternate fact), then these questions no longer make much sense, ordinarily speaking.

Mingwei Samuel of Safe Street Rebel:

I think we’ve ended up in a classic situation where people who are fans of tech end up pointing to a new tech thing and saying ‘this is gonna solve all our problems’ when it’s already a solved problem, when the solution is to design streets around people: fund transit instead of designing them around cars.

<3

hey nico, just stopping by to say i'm honored to be in your "hyperspecific collection channel" <3 i've been loving this channel for a long time. it's like a happy gold mine.

Haha I’m honored that your honored! Your channel is really entertaining, I’m a fan

Paul Ford:

I get asked a lot about learning to code. Sure, if you can. It's fun. But the real action, the crux of things, is there in the database. Grab a tiny, free database like SQLite. Import a few million rows of data. Make them searchable. It's one of the most soothing activities known to humankind, taking big piles of messy data and massaging them into the rigid structure required of a relational database. It's true power.

Paul Ford:

I've always loved that moment when someone shows you the thing they built for tracking books they've read or for their jewelry business. Amateur software is magical because you can see the seams and how people wrestled the computer. Like outsider art. So much of the tech industry today is about making things look professional, maybe convincing Apple to let you into the App Store to join the great undifferentiated mass of other apps. That's software. When people build their own Airtable to feed the neighborhood, that's culture.

Paul Ford:

Code isn't enough on its own. We throw code away when it runs out its clock; we migrate data to new databases, so as not to lose one precious bit. Code is a story we tell about data.

[...]

But programmer culture tends to devalue data. The database is boring, old, staid technology. Managing it is an acronym job (DBA, for database administrator). You set up your tables and columns, and add rows of data. Programming is where the action is. Sure, 80 percent of your code in Swift, Java, C#, or JavaScript is about pulling data out of a database and putting data back in. But that other 20 percent is where the action is, where you make the next big world-shaking thing.

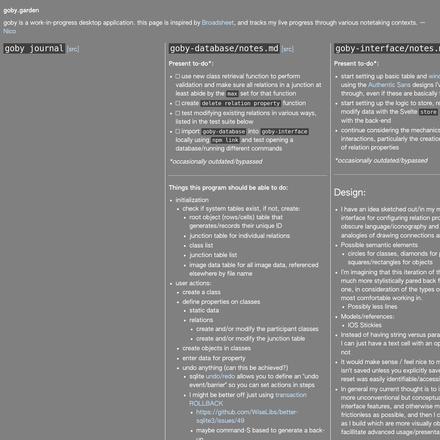

In re-designing the goby database architecture to address earlier limitations, I’m learning new things about what my original idea entails logically (things which the old database architecture failed to capture adequately).

The idea that I should be “discovering” new things in trying to map a logical schema is really amusing to me — it’s logic, so in a sense it’s all there from the start, waiting to be deduced from fully available information. But of course there’s only so much I can hold in my head at a time, so things never occur to me or I assume they’ll work out at first. As a result, I have moments of ‘discovery’ when I realize implications of what I’m trying to do.

Commercially viable websites often seem to have the weight of the world on them: they’re a big investment and the public face of an organization, and to that end they have to be extremely robust, functional, refined, and cohesive.

Accordingly I’m finding it’s a joy to be able to work on small, one-off editorial web projects, where the room for play and experiment is much broader, although the design decisions still have to be well-considered.

re: spinny cloud on mix-blend-mode: multiply

yes! I was thinking of setting it to multiply but the way the white background changes was compelling hh

hehe agreed! was that the result of the process you used to create/digitize the drawings, or did you manually change the background size?

more of the former — it was sketches all on the same piece of paper that I repositioned

(so that it'd stay centered haha)

ahhhh, I love that

Stuart Bailey:

The ICA has so far resisted the drive towards lowest-common-denominator programming that countless institutions adopt to attract the highest audience numbers. And likewise, we have aimed to avoid the bland, diluting effects of design-by-committee industry defaults that precipitate the easy slide into monoculture, instead championing the idiosyncratic and particular. In the ongoing drift from physical to digital means of channelling information, holding specific information in suspension with a generic template is not getting any easier, but it is a necessary job lest we are shortly made redundant ourselves...

Stuart Bailey:

An emphasis on the non hierarchical, parallel programming of the ICA's five main strands of activity, again to emphasise the multiple arts while acknowledging the fact that they run at very different speeds. In a typical season, there are anything up to eight different films playing in the cinemas every day, maybe one talk or learning event a week, one live event a month, and a daily exhibition that runs for around three months. A useful visual metaphor here was a motorway, with vehicles moving at different velocities along its various lanes, enacted most prominently on the website.

When we say the only way to get better at something is practice, I don’t think “practice” can be conceived as merely doing it the same way over and over — practice makes permanent, not perfect, as is said.

What we want to capture when we say that, I think, is that by doing something enough, doing it poorly many times over, you (hopefully) start to scrutinize and validate your own methods, course-correcting over time.

There’s an idea from Dan Michaelson that has always stuck with me, that a website can be a really interesting place to begin an identity system, because it asks you to think about how (typo)graphic elements apply to different content types and formats. But in recent work I’ve been realizing that the constraints of web aren’t always generative — it feels like they sometimes confine my thinking to treatments that are easy to templatize and build in code. I’ve been conversely deriving joy from starting first with static compositions, and then challenging myself creatively and technically to adapt them to dynamic surfaces like the web.

Jonathan Crary:

It's as if now we're at a moment where there isn't even the semblance of a coherent project of shaping consciousness. Instead, we're in an increasingly chaotic field. There is this acceleration, or this abruptness, and this kind of incoherent flood of completely incompatible, constant information.

So rather than building a coherent set of assumptions and ideas, we are inhabiting a world in which exchange and conversation and communication is... I don't want to say prohibited... but disrupted, in ways I can't think of as having any historical precedents. The diminution of any sort of historical memory on the part of an average person has being going on for some time, since the 20th century. Now there's a combination of damaged memory with the inability to absorb and assimilate how the present is configured.

Adam Michaels of IN-FO.CO:

I think if everything we were doing was extraordinarily complex we would go crazy, and I think if everything we were doing was extraordinarily simple we would also go crazy, so I think the key is always having a range of complexity and also a range in the scale of projects. Some projects we do are two years long…and it’s great to have that going on but it’s also nice to have the kind of thing where you can do the whole thing in 3 months, start to finish.

I think philosophy papers, produced as they are under the pressure of answering all possible objections and staying within a well-defined scope, sometimes trade clarity and persuasion for accountability and exhaustiveness.

I don’t know whether that’s a good or a bad thing, but it at least informs my decision as a non-academic about what kinds of philosophical prose I ought to invest the most time in reading.

I wonder if one solution to this would be the approach taken by Edwin Curley in Behind the Geometrical Method, which, as the description states, is “actually two books in one”: first, a clear and explanatory account of Spinoza’s arguments geared towards first-time readers of the Ethics, and secondly a text comprised entirely of the footnotes to the first section, which defend its interpretation of Spinoza in richer detail for other academics.

“out-thereness”:

When I think of “objectivity” or the question of what makes something an “object,” I often intuitively lean on the idea of “out-thereness”: that is, the idea that objects are those things which are out there, being as they are independently of us grasping them so.

This is, I’ve found, an incredibly fraught notion. But maybe one worth holding onto and expounding nonetheless.

Through the cyclical retracing of lines of inquiry that this platform enables, one observation I’m making is that my interests over time have gravitated towards the interplay or tension between what is ‘objective’ and what is ‘subjective’ (or how we should even conceive of those properties).

Thinking particularly of the trains of thought represented by

and

Elizabeth Anscombe:

The constant characteristics of Wittgenstein’s writing are close reasoning and strong imagination. But the book has also the character of great variety of tone: this is a rare character, and particularly rare in philosophical writing. (The only other examples I can think of are some of Plato’s dialogues). You get long passages of very sober, straightforward enquiry and argument; then a burst of breathless dialogue (always, of course, between himself and himself); sudden turn of humour, passages full of passionate feeling; pronouncements reached after perplexed enquiry, which have the air of being written with that feeling: And that settles everything; pieces of delicate, accurate characterisation of some particular temptation; remarks that are like a grasp or cry of realisation. And you get certain themes, certain moods recurring and recurring with different variations. I have long been tempted to compare this book with a musical composition; but hesitated to do so, until I found it elicited this reaction independently from someone who read it de novo.

Elizabeth Anscombe:

The final product of all this work has very remarkable literary qualities; once it is published, I think there will be no more wonderment why Wittgenstein –who spoke English well –wrote in German. It was horribly difficult to translate. I doubt whether much of a reflection of its style would be possible in English at all; at any rate it was not possible for me to achieve it. In general, German has possibilities of a homeliness –the very epithet sounds horrid in connexion with English –that is not in the [slightest] in conflict with the highest literary style. For an example, you only need to look at Gretchen’s lines in Faust when she comes in after Faust and the Devil have been in her room. Wittgenstein’s German is at once highly literary and highly colloquial. Good English, in modern times, goes in good clothes; to introduce colloquialism, or slang, is deliberately to adopt a low style. Any English style that I can imagine would be a misrepresentation of this German. All I could do, therefore, was to produce as careful a crib as possible. I bent over backwards to write in a spare and compressed English, since the German is spare and compressed; and in part I the translation turned out several lines a page shorter than the original. (This was right, because English is a shorter language than German)

Elizabeth Anscombe:

‘I spend more time than you perhaps could ever understand, thinking about questions of style,’ Wittgenstein once said to someone. The state of the MSS and TSS that he left behind him are a witness to this. He wrote an enormous amount; he threw away a good deal, and what is left is a formidable quantity of MSS written from 1929 onwards. He would often write first in small notebooks, then transfer siftings from these to larger ones, then further-polished-siftings to still larger ones. Then he would dictate to a typist. Then [he] would cut up the typescript and throw a lot away, and try different arrangements of the rest: for he always wrote in the form of isolated paragraphs capable of rearrangement. A great part of the material of the Philosophical Investigations exists in two other quite different arrangements, each brought to a final form and ready for the printer, and each elaborately cross referenced; for he hoped at one time to supply his ‘Remarks’ as he called them, with cross references to every other one with which he saw a fruitful connexion. His MSS. sometimes contain remarks written over and over again in various forms. They always contain a huge number of variant readings, with variant punctuations; and if you read carefully through each possibility, you notice how sharply aware Wittgenstein was of small rhetorical differences.

Elizabeth Anscombe:

A certain amount of current philosophical discussion concerns itself with linguistic usage. This is a direct result of Wittgenstein’s teaching that in a great many cases, in which we speak of ‘meaning’, though not in all, it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in the language. But use is not usage; he did not wish to base anything on idiom. ‘I distinguish,’ he wrote ‘between the essential and the inessential features of an expression. The essential features are the ones that would make us translate some otherwise unfamiliar form of expression into this, our customary form.’ What is or is not correct English usage is of no conceivable philosophic interest; nor does it matter if I choose to use words in an extraordinary manner, so long as it [is] clear what I am saying.

Elizabeth Anscombe:

The Tractatus is of the greatest possible importance for understanding the ‘Philosophical Investigations’. W. came to realise this and wanted the two books bound up together, which will, I hope, be done in a purely German edition. It is important because Wittgenstein clearly remained in love with the thoughts of the Tractatus, though he attacks and most powerfully undermines them. The Tractatus haunts the Investigations.

Are moral questions matters of fact, matters of convention, or a secret third thing?

A.G. Sulzberger:

Recognizing that journalists inevitably carried personal biases and blind spots, Lippmann called for controlling them by professionalizing journalistic processes and, in particular, embracing lessons from the scientific method. He entreated journalists to focus as much as possible on facts and to actively pursue evidence that could challenge, rather than simply confirm, their own hypotheses. In this conception, words like objective and impartial are not a characterization of an individual journalist’s underlying temperament, as they are so often misunderstood to mean, but serve as guiding ideals to strive for in their work. “The idea was that journalists needed to employ objective, observable, repeatable methods of verification in their reporting—precisely because they could never be personally objective,” Tom Rosenstiel, coauthor of The Elements of Journalism and one of the leading defenders of the model, explained in 2020. “Their methods of reporting had to be objective because they never could be.”

Hasok Chang:

I think we need to lose the thought, first of all, that the universe is a chicken.

Hasok Chang:

Every time I think about [GPS], it’s just incredible, how does this thing work? But it does. What they have to do, if you don’t know, is coordinate a whole set of geosynchronous satellites which they fly using good old-fashioned Newtonian mechanics. And then they put atomic clocks on these satellites that track the exact differences of time that different signals from different satellites take to go to a place and come back. And then these atomic clock readings have to be corrected using both general and special relativity — not together, separately — because there’s time dilation due to speed and there’s the change of clock rate depending on the place in the gravitational field. And then the signal gets beamed down to you and me, and we just walk around with our phones pretending that the world is flat.

All of these material, conceptual things have to be brought together in an incredibly harmonious way in order to make this whole activity of satellite navigation work. So roughly speaking what we’re talking about [with operational coherence] a harmonious fitting-together of elements and aspects of an activity that is conducive to the successful achievement of the aims of the activity in question.

It’s not that I think LLMs are conscious — only, I haven’t seen any good arguments for why on principle they couldn’t be, although this is often treated as a hard fact.

Ezra Klein on how AI shifts the relationship between intelligence and human worth:

I think these things [LLMs] are clearly, whatever they are, intelligent. They working with information in a problem-solving way. I’ve been wondering, why are we so scared of giving up the term ‘intelligent’? Why are we so afraid that something else might get called intelligent? And I think it has to do with how much we’ve made that the dominant way in which value humanity, particularly in a secular dimension. Why is it okay that we treat cows and chickens and the natural world in the way in which we do? Well, ‘we’re smarter, I guess?’…So then if you give that up, if you believe these things are intelligent and maybe they’re going to be more intelligent in so many dimensions than we are, then you’ve lost something profound.

But if that’s not how you value humanity, if you don’t think the worth of a human being is their intelligence — which on some level we clearly don’t, I mean children are wonderful not just because they might become smart one day… — there is something about how much we have dehumanized ourselves that I think is getting laid very bare in AI discourse. If we have such a thin ranking of our own virtues and values that these programs can destabilize it so easily given how limited they are, I think it’s getting at something which is a little discomforting, which is that we have valued human beings very poorly. And it would take a lot culturally, and call a lot that we have done into question, to value ourselves and other creatures in the world differently. But if we don’t then we have no defense against the psychic trauma of this thing that we’re creating.”

[...]

I think there is a lot of barely submerged guilt and shame, and truly vicious judgement of ourselves in a lot of the conversation [around AI]. I think some of the fear is that if you created something smarter than we are, it would treat us the way we treated everything else.

An interesting discussion of the idea of spontaneity in creativity:

Ezra Klein: To be McLuhanites for a minute, if the medium is the message — if the medium encodes certain ways of being and thinking that change the people who use it — what do you think the message of the AI chatbot medium is?”

Erik Davis: Wow that is an extraordinary question. I must admit I’m spinning a bit here...

EK Let me try one on you: something that I think is very present in the way people are thinking about AI is the idea that the output is what matters, and that the work of knowledge and of creation is this kind of, ‘you run a search on the information in your head, and then spit out the output’. There’s much more, I think, if you pay attention to yourself as a human being, mystery in that process. For instance, the work of writing a bad first draft is not just a waste of time on the way to a good fourth draft. It is often an intellectual space in which you realize you shouldn’t be writing that draft at all, in which you realize you should be doing a totally different piece, in which you realize something you never thought of or that something which isn’t in the ‘training set’ for that draft is actually relevant here. And it’s that mysterious intuitive sense that leads to great work or oftentimes just decent work... That idea that we can just outsource that — I think it’s a way of thinking ourselves as computers, as opposed to the more slightly mysterious creatures we are...

Erik Davis: It’s remarkable the way in which [AI] is an invitation to let go of a certain space of the unknown, the mysterious, the novel, the unpredictable in our own minds. And perhaps one scenario is that it becomes clear that these [machines] are insufficient, and so we honor that aspect of ourselves even more. But there’s also the possibility that it wasn’t necessary all along. And it is easy to imagine a situation where we become used to off-loading more and more decisions, and thereby accepting to ourselves that we too are predictable machines. So I think part of that message has to do with prediction and pattern, and what is in us that is not unpredictable, that is not pattern. Can we isolate that? Can we put our finger on it?...

I really appreciate Ezra Klein’s point here, which he attributes to Ted Chang, that as a process writing and most of what we think of as creativity is better understood as an iterative procedure, as opposed to a flat synthesis of information.

However I take issue with the way he then attributes this to the “mysterious” part of humans, and the way both him and Davis speculate about some special ingredient of human creativity that makes it hard to predict.

Klein's iterative account of creativity speaks well to our human experience of making things, but it doesn’t necessarily prove anything about the fidelity of human creative output compared to machine creative output. To think of humans as possessing a spark of unpredictable ‘spontaneity’ is to mistake the unknown for the supernatural. We are, to the extent that any phenomenon is predictable, completely predictable. That said, whether LLMs turn out to be the specific technology that can simulate our behavior with high accuracy is a different question.

British geneticist Steve Jones:

I’ve been sending the exam question ‘what is a species?’ to my students for fifty years, in the hopes that one of them will tell me what it is, because I don’t know!

[ Melvyn Bragg cuts in: “That's a bit of a cop-out answer!” ]

If they do tell me, I fail them. A species is an odd concept, because first of all, it’s a descriptive concept. I happen to work on a particular snail — most beautiful and charming organism — which is small and yellow and has got black stripes on it, and it’s called cepaea nemoralis. There’s a related species called cepaea hortensis, which can’t exchange genes with it — they don’t hybridize! So on that definition, they are different species even though they look almost the same.

Of course we have the mirror image of that, in which we have, say, the species many of us claim to belong to: homo sapiens. If we were to come from outer space and land on the earth in the middle ages, and go to Africa, China and Europe, it would make perfect sense to say you have three species of humans on earth. But that doesn’t work — it works only in the very shallow sense.

What you need is a biological definition of species, and the standard biological definition — which again, doesn’t work very well in the end — I think of as a ‘republic of genes’: if you’re a member of one species, you can exchange genes with any member of that species, either directly or indirectly (i.e. through several other individuals), and if you’re a different species, you can’t do that. That works quite well, but it doesn’t work perfectly.

I started cleaning my are.na index and pruning some defunct channels (it is spring after all), but I find myself wondering if it makes sense for me to do this, given the way I use the platform:

Oftentimes I make throwaway channels with 1 or 2 (or 53) blocks. These channels are less like collections and more like expressions: jokes or commentary in channel form, made for the purpose of self-amusement.

I don’t really consider these to be in the same category as the channels that I more regularly add to and modify, and which are more reflective of patterns in my thinking. But I don’t want to delete the throwaways, and unfortunately are.na doesn’t currently give me the tools to represent and place them differently.

There is, of course, the trick of preprending symbols and special characters to the names of channels. I used to do this and stopped because of a few reservations: it feels a bit untidy, and it interferes with the act of authorship involved in naming the channels, which is a big part of what I find fun about making throwaway channels in the first place.

But maybe I could just use special characters to organize my more central channels, and then leave the throwaway channels without any characters, that way they’ll stay together in an undifferentiated stream.

A.O. Scott on film critics as companions:

I started reading movie criticism as a way of, in effect, having someone to talk to since I was often going to movies alone. [Critics] were seeing what I was seeing in different ways, which was always very interesting to me — to go to a movie which I thought was great and then have it unlocked for me, or have my regard for it challenged… I’ve always thought that’s what criticism is and that’s what a critic is: not necessarily an expert or an authority, but a companion.

One idea that has been coming up a lot in my work and in conversations with people is that the effectiveness of an interface is often a function of the context in which it appears and is used, rather than its formal qualities.

For example: when someone is casually browsing, they have a lower tolerance for friction, complexity, and unexpected behavior. On the other hand, when someone seeks to be empowered or challenged — e.g. when they install a tool, follow a learning guide, or play a game — they might tolerate or even expect a learning curve in order to unlock the full capabilities of the interface.

Maybe this is just a rehash of the idea of “user journeys” but it’s been a useful thing for me to keep in mind.

I’ve been thinking about how to open up the time and conditions in my life for self-driven work and activity: “personal” projects, careful reading, research, and so on.

“Routines” seem to be one typical way of approaching for this kind of thing: setting aside fixed amounts of time each day or week, perhaps at certain opportune times, to work. I think there are some merits to this. One of the most valuable suggestions I was ever given in this vein was from my thesis advisor, who suggested we spend at least 15 minutes a day working on our projects, just to keep them in our minds and prompt us to make progress. That task of pushing yourself to stay in the right mental spaces, encouraging yourself to think along interesting lines and resisting the many distractions of our world, is really important and generative.

But I’m starting to think that particularly for more creatively oriented work, routines are the wrong organizational framework, or at least an insufficient one, for making really tangible progress and meeting goals on tasks without any deadlines or pressure. At least in my experience, working in small tidbits and dividing my attention between multiple high-investment activities keeps me from getting anywhere with anything — I need to focus for extended periods of time on individual tasks, sometimes reinventing my approach during the working process.

Setting goals and self-imposed deadlines for yourself seems to be another common approach, but I find it has its own issues. What happens when these goals and deadlines start competing for your time with important professional benchmarks and deadlines? You don’t have much choice but to set your personal goals aside, because there are no (immediate) repercussions. And in this process the act of self-imposing deadlines becomes less and less significant, less and less obligational, at least in my own practice.

So at the end of this, here is the idea I just had: what about instead of trying to distribute my time between many high-investment projects, I focus on one external thing at a time, see it to completion (with no deadline) and then move to the next? I keep each activity at a scope which makes it more than trivial but still surmountable. Some examples:

- reading a difficult text carefully, i.e. multiple times over, and taking the time to write notes/responses/reflections (I find this is necessary to get a substantial return on reading)

- a “tiny project” along the lines of the Tiny Projects blog

- researching and writing an essay (keeping a partial list of ideas for this here)

I could also try to split larger project ideas that I have into smaller, standalone projects that can later be combined, e.g. designing a book collecting essays I’ve written over a period of time.

One thing that occurred to me from a recent conversation is that reading behaviors aren’t solely based on the reader or the text in question: clearly the intended function — i.e. the relevance of the content in a specific context of use — has a large bearing on how someone will navigate, such as whether they need a linear guiding structure or whether they’ll be more inclined to click/flip around on their own.

For example, a student in a history class versus a researcher navigating a historical database: the former might find some sort of curation more useful, whereas the latter might just want to quickly identify specific pieces of information.

When I read things online, I often find myself pinching to zoom in on the text column in my browser. I’m not sure why I do this — I don’t think it’s a vision problem (although I do suspect I may have some very slight nearsightedness).

But regardless, I’m not inclined as a designer to design websites where the text is large and spans the full window — this can feel a bit claustrophobic for long passages.

I think there’s something in the act of pinching to zoom: it exerts some control over the page, changing the viewing frame from the one that has been anticipated and chosen by the designer for that window size. Maybe there’s an analogy there to the sense of freedom, when reading a physical book or article, to position and navigate the pages in a way that is not necessarily prescribed by the designer, although it may be suggested by them.

definition as explanation versus definition as identification:

A definition may be useful in explaining the sorts of thinking and activities that go into design, and at the same time be useless in differentiating design from non-design.

Liam Bright:

I am not sure what I think the significance of philosophy being a humanistic discipline should be; but a consequence of it is that we can be very open about consciously striving for aesthetic goals, in a way that might be uncomfortable for a scientist outside of pure mathematics or high theoretical physics. As such, I have never made any secret to my friends and colleagues that I take the aesthetic element of writing very seriously; but I am always somewhat embarrassed about this, because it has to be admitted that I simply do not have a very refined aesthetic sensibility.

Michael Rock:

I would not differentiate between language and design in the way I’m talking about it right now. I would say design is just an elaborate form of writing. So I think that they share exactly the same qualities and functions and I would say the difference right now is that in a culture where ideas are often distributed visually, [design] has a certain kind of poignancy or power because of that form of distribution, but I think that the categorization effect of design is exactly the same as the categorization effect of language.

Michael Rock:

Coherent systems are based on shared belief, and that belief is reinforced by physical evidence — we believe it’s true because we can see that it’s true. So as designers, our job is to provide that evidence. I think as designers you basically have two positions when you start a new thing: either you reinforce the system or you overturn it.

Michael Rock:

[Gendered bathrooms] are often thought about as a signage problem, but I would say it’s really an architectural problem, because this idea of the bi-morphic room is really an idea which is established architecturally, and then it’s developed by things like the ADA code and the uniform building code that determine certain kinds of architectural results that need to happen to address certain kinds of social conditions.

But it’s important to remember that it wasn’t so long ago that in big parts of the United States, there wasn’t two doors, there were three doors. The ‘colored’ door was neither male or female, it was a different category altogether. The fact that there’s two doors gives an explicit life to the category. It’s real because we’ve designed it to be real, and it’s not until you overturn the design problem that you can start to see the manufactured structure underneath it.”

I still hold to the idea that a conceptual scheme acts more as a way of discovering/predicting facts than a form of knowledge in itself — I'm not sure where Goodman would stand on that.

When a categorial scheme fails, it does not mean that it is “wrong” or “false” so much as irrelevant within a particular context, while potentially still relevant in other contexts.

I think this holds true in the case of the form/content distinction (whether you’re talking about Kant and Quine or Beatrice Warde and Michael Rock).

I was first enlightened by James’ squirrel parable in that it explained how ontological questions could be resolved into questions of semantics or conventions rather than matters of fact. But the realization I have come to more recently is that matters of fact are just cases where the semantics are undisputed, or at least not recognized as disputed.

In managing/planning a project, I often find that I begin with a set of categorical distinctions but then as I take notes they quickly break down — e.g. I divide notes on the “content” and the “design treatment” but in writing things about content, I find I need to expand on relevant aspects of visual form and materiality.

Ocean Vuong:

Sometimes I write a poem and I don’t realize what tense I’m using, or I’m writing a passage, and I have to decide later. Editing becomes the place where the past and present start to connect. When I’m writing, the curiosity pulls me forward. The work gets done when my terror is outpaced by my sense of urgency to speak. When there are good days, I go a little faster than my terror, and there are bad days when my terror beats me, and I’m silent. That’s the negotiation.

Hi Selina! Yes indeed haha, so happy you enjoy it :-)

Thankfully I don't have to do it manually — I wrote a short program to do it that relies on Eleventy, the tool that I use to build my site, the are.na API, and Netlify, which automatically refreshes it every 24 hours