Trying typefaces is like trying locks, including the feeling of sweet relief when you find one that works.

Writing requires us to be linear, and yet our ideas are typically nonlinear. So when we write about something we’re not somehow transcribing the conceptual structure of our thought. Instead, we’re giving the reader a toolkit to produce the structure on their own.

A common observation I’ve seen people make is the double-meaning of “meaning”. You might see this as the difference between the meaning of a statement and what a person means to me [1]. I.e. the difference between semantics and importance/value. I have a suspicion that there is something vitally important about the way these two “meanings” share the same word, and the ambiguity with which we employ the word. But I haven’t quite teased it out yet.

1 - I’m borrowing this framing from Cavell in his essay Music Discomposed.

Meaning is use and thus use can change meaning.

If you accept this, one question might be: when is it better to invent a new term for something versus transform the meaning of an existing term?

I wonder how accurate it would be to say factual information and emotional impact are more easily conveyed in audiovisual formats, whereas when it comes to understanding a concept, plain writing is typically better.

What does it mean to attempt to make something despite knowing it will be useless or obsolete? I’d argue it’s a bit like acting as if you have free will, despite knowing everything in the universe is determined. Or investing the world with meaning, despite knowing everything is meaningless.

(which is to say, perfectly admissible and rational)

One of the funny things I’ve noticed when working on many types of projects at once is that each activity becomes a joyful escape from the last.

At one moment I’m thrilled by the idea of spending hours on end programming a web page while listening to music and intermittent podcasts.

But as I approach the finish line, getting exhausted with this task, it feels as if something is missing. I no longer have the sense that I could spend the rest of my lifetime happily coding away.

In that moment the idea of spending my time reading a philosophical text, or writing an essay, becomes highly appealing. It fills a void, in the form of deep thought and consideration, that doesn't isn’t attended to in the act of making.

And then after long enough just reading and writing, I start to revert back to my original state of wanting to make something, something dynamic and functional and engaging like a webpage.

This sounds like a ‘the grass is always greener’ sort of thing, but it’s different. At each stage I am fully absorbed by the activity at hand, at least for the extent it takes to complete the project. And the exhaustion sets in only at times (like now) when deadlines force me to compress a lot of work into short periods.

As faulty as it is to not protect your life outside of work, I think it’s equally faulty to frame life and work as diametrically opposed, mutually exclusive.

I like that Spotify’s ‘liked songs’ playlist is by default ordered by date added — I can look through the additions like rings on a tree or layers of earth, reflecting the changes in my emotional state and musical taste over the years that I’ve used the app.

Is all empirical explanation grounded in correlation at bottom?

"why" vs "under what conditions":

I think the qualia objection is worth taking seriously, although it has to be very, very narrowly bracketed:

With science we can in theory come to understand and accurately predict when, how, and if someone will have a particular experience. The one thing scientific explanation cannot describe is “how it feels” to feel something (to someone who has never felt it before) — that is the only qualia problem. Even to this, there’s a caveat: I don’t see why it wouldn’t be theoretically possible to stimulate a person’s brain to have an identical sensory experience to that of another person.

The logical possibility of an experience not corresponding to its physical footprint is not really a problem for a naturalist, any more than the logical possibility of things falling upwards is a problem.

But that last point also reveals something interesting, namely that we don’t just run into this apparent explanatory limitation with qualia. Going back to Descartes in his letters to Princess Elizabeth, it’s been clear that scientists can’t really answer why there’s gravitational force, other than by identifying under what conditions there’s gravitational force. And really, this latter answer is entirely sufficient for most things in life.

Questions like why there’s gravity, why there’s qualia, why there’s a universe at all, are the same in that they probably have no satisfactory natural explanation, and they also don’t matter at all for anything ever.

You don’t need the answer to a question like “why are there qualia” to answer the question of “is there life after death?”. All the brain patterns which we associate with conscious experience are halted in death, and we have no evidence of them continuing in any other form. Ergo, it’s perfectly reasonable to assume that when you’re dead you’re dead. It’s as reasonable to assume that as it is to assume the sun will rise tomorrow.

And before any supernatural scheme of explanation tries to pounce on the apparent holes in scientific explanation, it has to be remembered that as soon as a theory claims some real-world effect, it becomes subject to scientific analysis. And in the capacity that it steers clear of real-world effects, it is completely baseless; it has zero explanatory force.

People seem to take issue with the fact that a naturalist/physicalist like Dennett freely acknowledges the reality of things like “information” that are not bound to a particular material identity (things that are “medium independent”, to use John Haugeland’s term). I think the core of his naturalism might be the simple claim that everything that’s real is explainable in physical terms, and predictable/observable using the scientific method. There’s nothing mystical about information in this sense; a piece of information is just an identification of a particular syntactic pattern or structure, which will follow consistent rules in any medium that can embody it: e.g., you can play chess the same on a physical board or on a computer. Moreover our values, morals, decisions, social constructs, etcetera can all be explained in terms of brain patterns.

It’s a shame the term “naturalism” is used so broadly as to lose its explanatory force, because its grammar offers a useful analogy. Naturalism for someone like Dennett is simply the refusal to admit anything super- natural into our explanatory scheme, which is to say everything real is within the realm of natural (scientific) explanation.

I gather that one part of the contrast between Chalmers and Dennett’s positions is the former thinks consciousness has a metaphysical status distinct from physical matter (but perhaps bound to a particular physical identity), whereas the latter thinks it’s simply a product of a particular syntactic composition, meaning you can switch it out for different materials, but as long as it’s the same in terms of what he calls “information”, it will be consciousness.

I sometimes rag on the formalist delusion that you can produce the same complexity of meaning found in language using only visual elements — images are crude, and there are so many cases where language does the job just fine.

But admittedly one benefit of communication through images is that it isn't confined to speakers of a single language. Within the scope of our shared human experience and global culture, a designer has a range of visual motifs at their disposal that are accessible to almost everyone.

There are many cases where I’d prefer that the decorum of a professional or academic title be downplayed in relation to the thing it names. The inverse, of course, is horribly obnoxious. But I don’t want titles to just match the dignity of their subject either; not only because that endeavor is doomed to failure, but because simple dry titles add an air of humility to a thing when it’s done exceedingly well, and also feel perfectly fitting when a thing is done adequately or poorly.

Timothy van Gelder:

It may be that the basic computational shape of most mainstream models of cognition results not so much from the nature of cognition itself as it does from the shape of the conceptual equipment that cognitive scientists typically bring to the study of cognition.

p. 432

A fundamental Cartesian mistake is to suppose, as Ryle variously put it, that practice is accounted for by theory, that knowledge how is explained in terms of knowledge that,, or that skill is a matter of thought. In other words, not only is mind not to be found inside the skull, but also cognition, the inner causal basis of intelligent behavior, is not itself to be explained in terms of the basic entities of the general Cartesian conception.”

p. 447

A thought following Collingwood and Wittgenstein:

A sentence isn’t really a “symbolic representation” of an idea. It’s more like a set of instructions you give someone for how to reproduce your idea with their mind.

I think the computational model of mind's proposal that all cognition is governed by overtly logical operations is dogmatic and overhyped.

However, I still think it's entirely conceivable to reproduce cognition/consciousness in a computer. Here is one conceptual proof of this:

Imagine in the future, we have a highly accurate scanner that can create models of the molecular composition of any substance. I.e., a device that can scan your brain and create a map of the positions of particles. Suppose we also have a program that can import that data into a 3d environment, and model the movement of particles.

Voila! Consciousness in a machine, through a brute force digitization of physical particles.

This is obviously a very programmatically expensive approach, and one that doesn't inform our conceptual understanding of cognition at all. However, if you accept that it's hypothetically possible to create a model of physical particles, and you don't believe in ghosts in the machine, I think this is a demonstration that it's possible to digitize cognition.

I'm tempted to give a definition of an ontology as a symbolic representation of ideas or information.

There’s a dichotomy between functional and aesthetic value that I often find challenging to navigate, because in this scheme I don’t know where to place what I call “intellectual” or “cultural” value.

By intellectual value I mean something that “turns your gears” — it gives you a new way of understanding something, which may not be practically useful, but seems to have more depth than mere aesthetic appeal.

It might simply be a subcategory of aesthetic appeal, because it produces an aesthetic pleasure in the state of understanding or contemplation.

two kinds of empowerment:

...the idea was to use computers to enhance human imagination — we called them imagination prostheses. And one of our metaphors was there’s two kinds of empowerment: there’s the bulldozer’s way and the nautilus machine way. The bulldozer way, you can move a mountain but you’re still a 98-pound weakling. The nautilus machine is a technology which actually enhances your personal strength, and we wanted to do the same thing for imagination. We want to make imagination enhancers: systems that help people become better thinkers independently of the system they’re using.

W.V. Quine:

The ultimate absurdity is now staring us in the face: a universal library of two volumes, one containing a single dot and the other a dash. Persistent repetition and alternation of the two is sufficient, we well know, for spelling out any and every truth. The miracle of the finite but universal library is a mere inflation of the miracle of binary notation: everything worth saying, and everything else as well, can be said with two characters. It is a letdown befitting the Wizard of Oz, but it has been a boon to computers.

I’ve often heard philosophical schools of thought described as “movements” — I doubt the terms are entirely synonymous, as there are plenty of movements that don’t involve any thought (only dogmatism). But at the moment I can’t think of a school of thought that couldn’t be called a movement, so perhaps the former category is entirely subsumed by the latter.

Tim Crane:

A picture may sometimes be worth a thousand words, but a thousand pictures cannot represent some of the things we can represent using words and sentences.

Blaise Pascal:

For in fact what is man in nature? A Nothing in comparison with the Infinite, an All in comparison with the Nothing, a mean between nothing and everything. Since he is infinitely removed from comprehending the extremes, the end of things and their beginning are hopelessly hidden from him in an impenetrable secret, he is equally incapable of seeing the Nothing from which he was made, and the Infinite in which he is swallowed up.

Does a definition with a disjunction (i.e. “something is an X if it fulfills either A or B”) lose its defining power? It somehow seems to make the definition weaker, though not by way of any weakness in the logic.

I think it’s because this would make the imaginary “essence” of a thing not one universal single thing, but a logical connective of multiple nonessential things. That is to say, A and B individually are sufficient but not necessary conditions. The ability to embody at least one of the two is the necessary and sufficient condition.

A necessary and sufficient condition does let you determine in all cases whether or not one thing is an example of the concept defined, so as far as distinction goes I think it works as a definition

But to your point, meaning is something that a necessary and sufficient condition doesn’t really capture. Circumstantially it may be true that all and only marsupials have baby pouches, but that doesn’t mean “thing with baby pouches” is an adequate definition for a marsupial

@patrick-yang-macdonald

For a while I was thinking of putting some photos of a pet on my website, but now I’m thinking otherwise.

I was persuaded through conversation with a friend that we ought not to expose the most intimate parts of our lives with the world at large. To paraphrase her: when we translate our personal connections and experiences into a form that is intelligible to others, something seems to be lost — we are impersonalizing them, robbing ourselves of the thing that made them ours.

I will still “overshare” on my future website as I do here, but only in the sense of sharing my ideas, opinions, and projects. These things are distinctive in that their significance isn’t (purely) idiosyncratic.

Maybe “idiosyncratic” isn’t the precise enough though, because I can imagine cases where I have an interest that no one else has, but it might still be worth sharing. By idiosyncratic I’m really thinking about the type of mundane experience or artifact that most humans have, which as a result would only be important to my mind or that of a creepy internet stalker. And purely is also very important, because I could imagine contexts where creativity in the presentation or insights about something mundane would make it worth sharing.

Historians are always thankful for little insights into a time period's human psyche. I remember reading a poem written right around 300bc from a mother to her kid, it was definitely a personal thing, like a diary entry—far from published, just preserved. I'm thankful for this random poem, even in 300bc moms thought baby hands were super cute. Maybe your creepy internet stalker will actually be a historian 1000 years in the future; glad to know that people have always thought certain animals were super cute.

Hmmm this makes me think that the mundanity of a personal thing, as in the prospect that no one could find it interesting, isn’t ultimately what decides if should be shared. Although I will say that there is an important distinction between recording and sharing— I don’t mind some future historian coming across my journal or personal photos on a hard drive.

So I guess my revised theory is there’s something malignant about the conscious act of sharing something personal. I have to think about how strangers will view this, and how that will transitively affect their view of me; the things I share become merely instrumental towards that end. If I publicly share things that are typically limited to my friends and family, it feels almost as if I cheapen those moments, artifacts, and relationships.

The difference to me between that and say, sharing a piece of artwork that features something personal, is that there’s something more than the personal artifacts that you’re sharing in that moment. Like the thing you’re sharing is the artistic expression, and the personal information is sort of tangential to it. Since the personal part isn’t the reason why you’re sharing it, it’s no longer problematic.

@leah-maldonado

The innovation of Are.na is the (near) communal ownership of any individual piece of data.

the original vision:

medium vs tool:

Does “don’t let anyone dictate who you are” have to be synonymous with “be yourself”?

I’d like to just “be”, independent of anyone’s oversight, least of all my own.

Robert Bringhurst:

If the book appears to be only a paper machine, produced at [its] own convenience by other machines, only machines will want to read it.

B.F. Skinner:

Every science has at some time or other looked for causes of action inside the things it has studied… There is nothing wrong with an inner explanation as such, but events which are located inside a system are likely to be difficult to observe. For this reason we are encouraged to assign properties to them without justification.

Categories can be exclusive because of a formal rule (e.g. if an item is in one category, it can't be in another), but they can also be exclusive as a result of arbitrary circumstances (e.g. none of my blue marbles are made of glass, but that doesn't mean there can't be blue-colored glass marbles).

This is something like correlation versus causation, but not exactly.

Siobhan Roberts:

Programmers still train the machine, and, crucially, feed it data. (Data is the new domain of biases and bugs, and here the bugs and biases are harder to find and fix). However, as Kevin Slavin, a research affiliate at M.I.T.’s Media Lab said, “We are now writing algorithms we cannot read. That makes this a unique moment in history, in that we are subject to ideas and actions and efforts by a set of physics that have human origins without human comprehension.”

Knowing the 'right' word for something can expand our world; but it can also contract it.

no such thing as true randomness?:

A graphics programming professor of mine made the note recently that everything in a computer is wholly determined, and thus there's no true way to logically compute randomness — only something so variable that it appears random, hence the term "pseudo-random". "Real" randomness in programming consists of measuring real-world data and using it as a seed to create entropy, such that different computers can compute random differently.

With determinism in mind, I think what this reveals is that something "random" is just something contingent on variables that we don't know or understand. We know and understand all the variables in a computer fully, so computers have to outsource data from the environment. But a "random" event in real life like picking a name out of a hat without looking is no different; physical and causal relationships determine which name gets picked out. If we were to understand those relationships with a much higher degree of accuracy than we're currently technologically capable of, we would grasp that it could not have been any other way (the same as in the computer).

on re-reading Kant and Descartes:

Re: block 13282702

I have to say a similar thing has happened in my philosophy classes too though. This semester I've circled back to my "roots", re-reading the texts of enlightenment figures that I read in my intro class back in sophomore year. I used to hate Kant, but I'm realizing now that I just hadn't read the part of his ouevre where he really tries to ground everything he's doing. His arguments in the Critique are as strong as bedrock (so far, although I think I'll ultimately still diverge from his picture of metaphysics and philosophy). On the flip side, I remember also being annoyed with Descartes' arguments but not exactly knowing how to prove him wrong. Now I'm able to more clearly see the holes in his arguments using the tools of 20th century philosophy (or just Kant).

But I'm simultaneously a bit more sympathetic towards him, and more sympathetic towards authors generally, because I've learned/been taught the virtue of "suspending your disbelief" as a reader.

I'm only now beginning to appreciate design criticism:

The comedic yet tragic thing about going back and looking at some of the texts I read for class back in my sophomore year of design school is that I've only just now started to develop a comprehension of and investment in what the authors were arguing.

The difference between today and back then is that nowadays I'm much more immersed in the dialogue and culture of design, to the point of developing actual views of my own. When I first read the texts, I was only just becoming acquainted with the tools and methodology of graphic design. Therefore the problem was, so to speak, that I didn't have a horse in the race. My focus was oriented towards improving my knowledge and ability, and I was more than happy to defer to what professors told me to think (although I'm coming to understand what they were saying better now too).

predictive classification systems in the sciences:

I'm often tempted to take a sort of harsh nominalist position: all our categorization systems are just human conceptual models mapped onto the undifferentiated soup of matter that is the world.

But the branching pattern of evolution seems to challenge that, because it provides a causal justification for distinguishing, if not between genetic ancestors than between species on different branches. I've noticed scientists sometimes get muddled in problems of (empirically) arbitrary categorization — like the question of whether Pluto is a planet. But contrary to my intuition, it may be that you can't call all categorization arbitrary. Another example is the periodic table.

Maybe one could say the controversial classification of planets is different from species or chemical elements in this way: the classes in the former do not hinge on qualities that make it possible to predict or explain things about their members. The periodic table, for example, was used to predict properties of missing elements before they were discovered.

In that regard, the planet classification system does absolutely nothing. It just takes existing information about planetary bodies, and group them into buckets using a semi-arbitrary set of rules. What you call Pluto doesn't make a difference in predicting things about its behavior. All the information is already there in what you know about the thing.

This almost seems to map onto a Kantian analytic/synthetic distinction!

In broad strokes, an “illustration” in written argument is a sort of example: something that applies the concepts from an argument in a real/imaginary situation so that you better understand what’s going on.

Why is it that this is useful? Some philosophers, famously Kant, would argue that it’s not useful and takes up space. The illustration isn’t the proof itself but something superficially added on, the reasoning goes, and thus the argument could work as well without it.

But my intuitive sense is that illustrations and thought experiments are extremely useful psychologically for grasping the argument. Why should this be? Why should the argument itself not be enough to make the point salient to me?

One answer that comes to mind is that there are unwritten assumptions in an abstract argument — things that don’t immediately occur to us until we try to think through the problem on our own, and run into the issue. The bare words themselves aren’t doing any work — we need to situate them in the world, where their meaning is informed by context.

Susan Kare on working under constraints:

This was my first time working with pixels, doing it on the screen. I really hadn’t designed anything on a computer, and I wasn’t someone who worked in grids. What became clear to me was that I really enjoyed the structure of that kind of design challenge, of working with relatively limited screen real estate. I went on to design icons which, unlike the font, had the element of symbolism, a different kind of problem to solve, because there was a concept along with the pixels. I still look for pixels in everything: Lego, needlework, mosaics. Cross-stitch fonts are a perfect analogy for what I was doing: There are 18th-century samplers that are perfect. And even though I work a lot in vector images now, where pixel count doesn’t matter as much, I still feel as though if you have that constraint, I’m your person.

One of the hats you can wear as a designer that I’ve always loved is being the expert in charge of production and distribution. I always thought this was a role only web designers played. But watching How to Make a Book With Steidl has revealed to me that its exclusion from print design is circumstantial. I find the idea of being a designer and printer like Steidl so picturesque and fascinating.

“Agnostic” in the philosophical sense is a bothersome term, but in the design/technology sense a very useful term (e.g. “platform agnostic” ). Similar to “unopinionated”, it describes a tool that works well in a wide variety of use cases or environments, rather than imposing a particular one on the user.

One important realization I made about note-taking, whether of texts or spoken lectures, is that the main utility (at least for the things I study) is not to record information that I’m going to look at later. I can barely read my own inarticulate chicken scratch, so that’s out the window. Instead, I write things down because it keeps me engaged in the subject, rather than passively consuming the material.

I remember reading a research paper in a psychology course about an experiment that measured people’s engagement in an experience, with the experimental variable being whether or not they were given cameras to take pictures. It surprised me at the time that those with cameras not only self-reported higher levels of engagement, but could actually recall more things about the experience from memory.

This seems natural to me now — the camera-takers were “all there”, as Professor Klein might say, pulling from John Dewey.

In retrospect I think the thing Quine is really getting at in Two Dogmas is the fact that in any usage of a sign, you need a criteria for when a sign is appropriate, and this criteria at bottom has to be synthetic (therefore there are no truly analytic propositions).

Of course that’s just a bunch of silly jargon that is intelligible to a very few and useful to even less. Which Quine is well aware of, and which makes the last couple sections of the paper (where he zooms out and talks about the web of belief) so much more compelling.

Do we experience continuous things as discrete, or discrete things as continuous?

Or does that dichotomy already presuppose human ontologies?

I think what Dewey crystallizes so well for me is how and why I find logical/intellectual experiences so aesthetically engaging, and similarly why I find materialism and the mechanical view of nature so beautiful and freeing.

John Dewey:

The material of the fine arts consists of qualities; that of experience having intellectual conclusion are signs or symbols having no intrinsic quality of their own, but standings for things that may in another experience be qualitatively experienced. The difference is… one reason why the strictly intellectual art will never be popular as music is popular. Nevertheless, the experience has a satisfying emotional quality because it possesses internal organization and fulfillment reached through ordered and organized movement.

John Dewey:

Thinking goes on in trains of ideas, but the ideas form a train only because they are much more than what an analytic psychology calls ideas. They are phases, emotionally and practically distinguished, of a developing underlying quality; they are its moving variations, not separate and independent like Locke’s and Hume’s so-called ideas and impressions, but are subtle shadings of a pervading and developing hue.”

We are all unreliable narrators when it comes to our own psyches.

Or maybe our own “cognition” would be better

In a logic and computing, nesting things in a loop (i.e., set A is a member of set B, set B is a member of set C, and set C is a member of A) is trivially easy. But off the top of my head I can’t think of a taxonomy of real objects where that would be applicable.

Despite every philosophy teacher I’ve had counseling temperance in reading philosophers I disagree with, I must admit there is a great joy in reading work that is at least thinking on the same wavelength as me, a feeling which, among enlightenment philosophers, I’ve only gotten from Hume and La Mettrie.

Wittgenstein is in some ways so alien to the western tradition that writing my first paper on him was agony, like doing a stretch that contorts your body in an unfamiliar position. I think the popular analogy between mind and muscle is quite useful, even if it isn’t scientifically accurate.

A way of thinking about reading that resembles the conceptions of La Mettrie:

The focus and dedication required to read for understanding is effortful, similar to how going on a run is effortful, and rewarding for the mind in the way the other is rewarding for the body.

Moreover, both achievements become less taxing through A) repetition, which strengthens the muscles required in either case, and B) proper form, which maximizes the return of one’s effort.

People and especially children tend to be overly skeptical of their capacity in one or the other, merely because they have not built up their ability through training. But on the other hand, natural talent can obviously give some people an edge, and extend the limits of their ability further than average.

I have no desire to be a visual rhetorician.

I'm of two minds about genealogies in philosophy.

On the one hand, I like that by historically contextualizing a concept, you can challenge notions that we take as a priori in contemporary discourse [1].

But from a more stylistic point of view, I find them very tedious and unrewarding to read. When a text consists of an author offering example after example illustrating the development of an idea, I'm not given any real incentive to maintain my focus. The only stylistic appeal of a genealogy is the amusement one derives from consuming anecdotes. Maybe it's a fault of my reading ability, but I find it very difficult to sustain interest or synthesize a conclusion from genealogies. These sorts of explorations seem much better suited to audio/visual formats like documentaries and podcasts, which I can intake while doing the dishes or taking a walk. They don't have the same logical complexity or continuity that reading is really well suited for.

. . . . . . .

[1] I find the same kind of appeal in science fiction, in the way it disrupts our everyday understanding of the world by showing how it depends on arbitrary states of affairs.

John Dewey:

The live animal does not have to project emotions into the objects experienced. Nature is kind and hateful, bland and morose, irritating and comforting, long before she is mathematically qualified or even a congeries of ‘secondary’ qualities like colors and their shapes…Direct experience comes from nature and man interacting with each other. In this interaction, human energy gathers, is released, dammed up, frustrated and victorious.

It occurs to me that my progress in exploring analytic philosophy has been semi-chronological; I started with Wittgenstein, then jumped to some 50s texts by Quine and Cavell, and now I'm looking at stuff from the 70s/80s by authors like Putnam, Kripke, Douglas Hofstadter, etc

The reason why it's difficult for me to put scientific descriptions and ordinary perception in equal regard is that the former can be used to predict the latter, but the latter cannot be reliably used to predict either the former or itself.

world-building in the broadest terms:

Tiger Dingsun and Nelson Goodman have inspired me to consider "world-building" in really broad terms, as the simple act of defining an ontology. You might say we engage in world-building when we: — organize a file cabinet — plan a daily routine — explain our jobs to people — create an outline for an essay — design a syllabus — build a template to be customized by others ... and so on.

I think this world-building has a sort of innate appeal to us — or to me anyway.

Like with fast food, sometimes the UX feature people desire is not the one they need in order to be healthy.

Diana Hamilton:

I really don’t want to write a bunch of papers

defending poetry from being so charmingly pointless. “Isn’t it great,” I could say, “that I spend my Sundays

doing the equivalent of writing love letters on a typewriter; I’m very precious, don’t you think, but don’t worry,

this is a ‘political’ decision, I’m claiming my droit à la paresse, as you know, sons know better

than fathers the pleasure of shirking work.” What sort of lie would this be?

Taste isn't arbitrary, and to say it's "subjective" is a bit oversimplified and relativistic.

I like to describe it as intersubjective. By this I mean that it's a product of biological and cultural factors, and is therefore shared with others to the extent that their background overlaps with ours.

Two neurotypical humans are likely to share a certain degree of their sensibility simply by virtue of shared genetics. For example, humans are naturally inclined to prefer symmetrical faces to asymmetrical faces, the evolutionary explanation being that symmetry is an indicator of good health.

Layered onto and sometimes contradicting our biologically acquired sensibility are many overlapping factors of human experience such as culture, family, life events, and so on.

@nico-chilla I like the direction this is going. Does this mean, then, that taste can be shaped? What role might designers play in taste-shaping—if possible (though likely not at the individual level... though with cult of celebrity who knows...)? What might incentivize a designer to take on a task of taste-shaping as a kind of moral endeavor?

** Maybe "re-shaped" is a better word than "shaped?"

@patrick-yang-mcdonald I’m sure taste can be reshaped and often is — trends in any artistic medium are proof of this to me. I’d consider the pioneers in the postmodernist movement of design (e.g. Cranbrook, Emigre) as examples of “taste-shaping” designers. Moreover the postmodernists were morally motivated to rebel against the design canon and the institutions it represented (e.g. Paula Scher once said Helvetica represented the Vietnam war).

I also want to remark that I don’t consider morality itself to be any different from taste; it’s similarly shaped by biology and culture, and it can similarly be reshaped through experience.

Rudy VanderLans on working at the SF Chronicle after going to school at the Royal Academy of Art in the Hague:

It was the complete opposite in terms of design from the way I had been educated and where I had worked before. There, design is seen as this really serious thing that can help save the world. Whereas the Chronicle broke every rule in the book; they did everything wrong according to what I had learned. It was kind of interesting to see that you could break all these rules and you could still have hundreds of thousands of people reading the newspaper and they had no problems at all with the fact that we were breaking all the rules.”

Paul Ford:

When I was like 6 years old, my father —who was an English professor but into computers — sat me down in front of a Commodore PET and said “look at this: when you write these little programs, they’re almost like little poems.

I wonder how Wittgenstein's ideas in the Investigations compare to the tenets of nominalism

Languages sometimes act like ontologies, with specific components like lego bricks which connect to one another in particular ways. If you connect them in a way that doesn't correspond to their ontological arrangement, the statement ceases to make sense in the language.

For example, the statement ∀x (→) in modal logic or Who door runs cartwheel? in English.

However, on the edge of my understanding there seems to be some distinction between the ontology in a language, and an artificial ontology. To illustrate:

A common feature request for Are.na is the ability to connect blocks directly to other blocks. This doesn't exist in Are.na's current ontology, because it defines channels as the only entities which can link to blocks. So, here is the rub: what separates asking for block-to-block connections from requesting that Who door runs cartwheel? suddenly make sense in English? Both are basically requesting that the rules of the respective ontology be rewritten to accommodate something new. However, to me the former feels much more sensible than the latter. It's as if in the former case, the ontology has more constrained limits than our thinking patterns, while in the latter, the statement just feels actually incoherent to us in a way that transcends the internal logic of the language.

I feel as if I'm missing a part of this, but can't even articulate what is missing.

The only kind of share button I ever appreciate is a copy-link-to-clipboard button. For whatever reason I don't like external services co-opting my manual process of sending someone a link with my commentary. Maybe I'm just paranoid after seeing share buttons that try to insert their own generic text into your post or message.

Anyway copying a link from the URL bar on desktop takes one click and one keystroke. The only way a website is going to remove friction from that is by eliminating the keystroke. On mobile this is actually really useful, because in absence of a keystroke you would normally have to do the annoying tapping/dragging thing to copy.

Modular design systems are fascinating to me, and I think it’s the same kind of appeal that Minecraft or lego bricks have: the infinite permutations to be made from a finite set of rules.

The trope is thinking outside the box, but I think one thing designers know is that it can be just as creatively invigorating to work within the box (or make your own box)

Can the relationship between object-oriented and functional programming be likened in any way to that between a file directory and an arena channel?

If I make an object with random strings for keys, is it still an ontology?

The world doesn’t have a back-end. But our brains certainly seem to.

I don’t like high-contrast serifs like Bodoni, but it occurs to me that this isn’t a form critique at all all — Bodoni’s letterforms are beautiful. I just dislike the air of luxury and pretentiousness that these typefaces have come to represent.

My preferred workflow of designing as I code is certainly disadvantageous in a number of ways. But the pace of projects in a newsroom sometimes means there’s no time to do prototyping upfront, which means I conveniently get to work the way I find most comfortable.

Design is indeed a mode of communication. But I think we’re all a bit confused about what communication is.

I don’t like dogma, but it would be dogmatic to say I’m fundamentally opposed to dogma

Now that I’ve partially resumed working outdoors, it occurs to me that ending each day without a walk home all this time has been like ending a sentence without a period.

Whoever came up with the parent-child behavior of position:sticky is a genius

Messages seems to have recently introduced the feature of choosing your own name and prof pic.

But I also think there’s something nice about the way it has worked for a long time: being able to personally contextualize contacts with our own custom names and photos for them.

There is a deep joy in discovering someone stating an idea you’ve had, better and more clearly than you’ve ever stated it.

Mindy Seu on interface as a place of discursion rather than display:

I see all these projects as case studies for how I want to view information online. And that is making it as comprehensive as possible, making it free and accessible, and connecting a lot of different references and writers and contexts .

How can we think of the interface as a place of discursion rather than display? Currently the internet is all about display and self promotion, and that is difficult to find your place in.

Charles Broskoski:

A phrase that comes to mind regularly for me is “The slow blade penetrates the shield,” a phrase from the novel Dune, spoken to the novel’s protagonist during a combat training session (please bear with me). I think of it because I like the notion that in the struggle to create something—to bring to fruition a project, a work of art, a company, whatever— sometimes the best strategy is slowness. Despite any feelings of impatience we’ve had during the lifespan of Are.na, I do have a sense that slowness has actually worked in its favor. It’s the reason why Are.na’s community is so singular. We’ve had time and space to become (slowly and with care) more and more ourselves.

I’ve fallen into pretty frequent usage of the word ‘ontology’, and I think at some point I’ll have to inquire about how exactly I’m using it. The formal definition as ‘nature of being’ seems too pretentious and metaphysical for my taste. I was thinking another way to describe an ontology might be as a way of ordering information. But it seems a little inadequate as well, in this way: an ontology is shaped around a particular, biased way of understanding the relationship between concepts. It’s not arbitrary, for example, in the way it draws the difference between sense and nonsense.

to be continued

I’ve been reading Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet to quiet my soul before bed, and he’s done an interesting thing of using both indentation and spacing to create two levels of hierarchy in the text (paragraphs are adjoined by indentation into a grouping, which is then separated from other groupings using spacing. I’d like to try this in a future piece pf writing.

I like web design best when I can just focus on the logic and geometry. There’s a point at which you have to interact with the messiness of the world: things like scroll detection and asynchronous operations. Those are truly challenging empirical problems with far less artful solutions.

Douglas Hofstadter:

This book is structured in an unusual way: as a counterpoint between Dialogues and Chapters. The purpose of this structure is to allow me to present new concepts twice: almost every new concept is first presented metaphorically in a Dialogue, yielding a set of concrete, visual images; then these serve, during the reading of the following Chapter, as an intuitive background for a more serious and abstract presentation of the same concept. In many of the Dialogues I appear to be talking about one idea on the surface, but in reality I am talking about some other idea, in a thinly disguised way.

Douglas Hofstadter:

Computers by their very nature are the most inflexible, desireless, rule-following of beasts. Fast though they may be, they are nonetheless the epitome of unconsciousness. How, then, can intelligent behavior be programmed? Isn’t this the most blatant contradiction in terms? One of the major theses of this book is that it is not a contradiction at all.

A machine “eats its own tail” when it “reaches in and alters its own stored program” [1]

I wonder if you can do this with javascript in the browser, by modifying the content in a script tag.

[1] from page 25 of Hofstadter’s Godel, Escher, Bach, where he’s describing the work of Charles Babbage.

Unopinionated tools and abstraction:

After discovering Eleventy, I’ve fallen in love with the idea of an “unopinionated” framework. This term is used by programmers to refer to software that doesn’t create a walled garden. But beyond that, I think there’s something generally interesting about the idea of building tools that don’t prescribe their own ontologies. I’m thinking of tools that don’t have a very specific use case in mind: they perform simple but powerful operations with a lot of room for customization.

These are the types of tools I appreciate as a user, and they’re also fun to build as an amateur coder/logician because they involve a lot of abstraction. Abstraction in programming is about atomizing a certain logical operation so that it only has to be written once, and can be used over and over again. It’s often joked that laziness is a good quality in programmers, because in order to write less code, they abstract operations to eliminate redundancy.

The more unopinonated a piece of software is, the more versatile it has to be, and therefore the more abstracted the code has to be in order to be efficient.

———

At the same time, my experience with anti-essentialism and interface design suggests to me that a truly “unopinionated” tool is a mythic creature. For example, I’d consider Are.na relatively unopinionated, but one could still argue it prescribes a particular ontology of blocks, channels, users, and connections. You need to put in some degree of framework in order to make the tool a tool in the first place.

In web design, should layout come before type choice, or vice versa? It seems like an impossible problem given their interdependency.

@anyone who builds websites, how do you prefer to work?

Creating inconvenience and discomfort is a valid design decision — under the right conditions.

It seems important to note that the same exact statement can be made about creating convenience and comfort — it’s also a valid design decision, but likewise only under the right conditions.

The relationship between research and creativity seems a little more complicated than the metaphor of input/output that's often used. I can read things that have next to nothing to do with my project, but it will still have a positive influence on my ability to work and come up with ideas.

My guess on why this is:

Reading is more than just transmission of information. A good text will prompt you to think on your own and reexamine your existing knowledge in light of new evidence. On the other side, the creative process involves conjuring up existing ideas and memories to "synthesize" into something new. Your creative output is therefore dependent on having those ideas and memories at top of mind. Reading helps by being a catalyst for general recollection and cognitive salience.

Why does finishing a tv series always hit me with melancholy like a ton of bricks?

Moore’s paradox:

An interaction with someone prompted me to remember W’s framing of Moore’s paradox, and it dawns on me that the phrase “I believe” is even more tricky than I thought on my first reading.

“I believe” is sort of logically untranslatable. If you “believe” something, you don’t just believe it, you know it to be true. As W notes, at first glance the phrase seems like something that could only be said about someone else.

What this reveals is that “I believe” is playing a particular role in a language game. My first intuition was that by saying “I believe”, you can state your certain knowledge while signaling your fallibility to someone. I still think there is some sense in which “I believe” is a performance of humility. But maybe the gesture is a little less complicated, presupposing a certain conceptual framework: “I believe” could be a way of stating certain knowledge without the connotation that differing beliefs must be invalid, which you would otherwise create by saying “I know” or simply stating the belief. If so, there’s a certain cultural perspectivism that underlies the phrase.

Contingency schedules:

The tricky thing about planning out one’s day of creative work in advance is that there’s never any guarantees. Every task is like panning for gold: maybe you’ll come up with something by lunch time, maybe not.

I feel as if my schedule has to be a flow chart to make that work: contingency plans for every checkpoint that may or may not be reached at the end of its allotted time frame.

I'm finding this essay astonishingly insightful and compelling

Tiger Dingsun:

We are already adept at invoking widely shared, conventional systems of meaning in order to make our work function on the basis of clarity, but it is also possible for clarity to exist simultaneously with another, murkier kind of effect that comes from fortifying conventional logic with a graphic designer’s own internal logic.

A more affectionate and pithy correlary to my last entry:

Returning to Wittgenstein (I’m perusing my new copy of On Certainty) is like meeting with an old friend after returning from a journey. His writing and worldview has certain peculiarities that I couldn’t comprehend on my first read of PI; but now after digesting his ideas and reading inheritors like Cavell and Anscombe, those quirks feel simultaneously familiar and eye-opening.

There is a kind of poetic spirit in the way Wittgenstein does not typically make his point explicitly — but not at all ambiguous in the way most poetry is. There is an underlying precision. He seems to know exactly what needs to be said to communicate the point, while sparing you the obvious and tedious explanations that most academic philosophers would spell out for their own satisfaction.

On Parfit’s teleporter:

It is suicide to use the teleporter, therefore so long as you fear death, you shouldn’t use it. That your atoms will be reproduced in their exact configuration at another location should provide no additional comfort to you; if you wouldn’t shoot yourself, you shouldn’t use the teleporter.

BUT as we’ve known since Epicurus, there is no rational justification for fearing death.

The teleporter problem is just a red herring.

There’s a fun recursivity to the way that some philosophers define, for example, a person as nothing more than what we perceive as a person. It seems almost shallow, but what it’s really trying to get at is the fact that there is nothing beyond the surface. All we can say is this or that quality makes it likely that we’ll see something as a person — we can’t claim that quality makes it a person or is the essence of personhood.

A peculiar challenge of creative work is that it relies at least in part on judgement (as opposed to reasoning).

You can work on something all day, hate how it looks, then come back the next morning and realize it looks okay. The work hasn't changed — only your mood and mindset makes it feel different.

It's similar to how you might hear a certain song or album when you're in a good mood, and love it, but then come back to it later on and realize it's not all that great.

Cups in a dishwasher:

For a cup in my dish washer, right-side-up is upside-down.

This is a statement with two meanings, depending on which term you take to refer to the normative context of the dishwasher, versus the normative context of every day life.

I could be saying A) A cup’s right-side-up position in everyday life is, in a dishwasher, upside-down or B) A cup is right-side-up in dishwasher terms when it is in normal terms upside-down

If you build the concept, the visuals will come

Theorem and proof as pearl and oyster:

Gödel’s incompleteness theorem “can be likened to a pearl, and the method of proof to an oyster. The pearl is prized for its luster and simplicity; the oyster is a complex living beast whose innards give rise to this mysteriously simple gem.”

— Douglas Hofstadter, Gödel, Escher, Bach, p. 17

Programming something from scratch without time pressure might be one of the most relaxing pastimes I'm aware of.

It seems to have a sort of unlikely affinity with worldbuilding.

In Octavia Butler's Dawn, aliens abduct humans and violate their bodies in various ways. By altering their biochemistry, the aliens make it so humans actually desire alien contact. The aliens claim that they won't do anything to the humans that they don't want. But despite this, they frequently disobey direct pleas by humans. Their justification is that they know the humans actually desire the contact, and so their pleas are "only words".

"Only words". This reduces what we call the will to mere desire.

Whenever I force myself out of bed early in the morning, I’m acting against my desire. In that case, my action has a utilitarian benefit measurable in terms of productivity. But in the world of Dawn, it’s less clear cut. One could perhaps say the humans are refusing contact out of sheer moral principle. This gives a sort of deontological picture: it is their sense of duty to principles in the face of their desires that makes their refusal moral. But they could also, and this is more likely, be refusing out of fear and stubbornness. For the aliens to ignore this and call it “just words” is to hold a very narrow construal of desire. But still, it is interesting to think of the aliens as enacting a model of utilitarian ethics: acting in the best interests of humans with no regard to their principles and values.

The lesson I take from people like Tracy Ma is that serious design only happens once you stop taking design seriously.

Is spatiality inextricable from reality?:

It’s easy to understand color as a peel-back layer of our sensory experience, because we can conceive of a spatial world without colors.

But when it comes to spatiality (extension) itself, we feel it is fundamental to the fabric of reality. Things like position and depth can be understood as no more than aspects of the way we perceive the world, but they are inextricable from our conception of reality.

One of the things that a philosopher can say to a skeptic of reality is that we have no reason to believe we are “living in a simulation”, and thus we can operate on the assumption that what is real is real. But the question that of course follows this is, what would count as a reason?

I’m inclined to say a phenomenon that somehow transcends the laws of physics. But that’s the type of thing that science tries to address by finding natural explanations or revising its own principles. Our own human unreliability is a constant factor as well: we can say we hallucinated or dreamed something.

So it becomes very difficult to think up some sort of rational standard that would definitively confirm our reality is an illusion.

Anthropologist James Suzman:

If I play on my guitar, it brings me pleasure, but I know nobody in their right mind would want to listen to it. Most people who write books generally write them for themselves, because you have to be very lucky to get read more widely than just a handful of people. We've lost a sense of the wonder and the joy of that kind of purposefulness.

Anthropologist James Suzman:

Work is very much a part of who we are. And when we are deprived of the ability to work, we are miserable, we are listless, we are bored, and in many senses life is not worth living.

[...]

It is obviously part of our evolutionary heritage: this ability to work efficiently and to apply our skills to acquiring the food we need...And then when we have surplus energy, we clearly use those same skills that have empowered us to be such versatile, flexible hunters, foragers, understanders of and environment, we apply those same skills to many other things...

One thing Mike Birbiglia says often that I like is that "you have to be a little delusional to make it as a comedian".

I find it really compelling as a maxim: if people think you're crazy for pursuing something with such low odds, it may be a sign that you're on the right track.

From a logical perspective though, it was a little confounding at first; how can you be delusional if you're right? But I think there's a way that it still works. If we use the popular (and imperfect) definition of knowledge as "true and justified belief", delusion can be said to be unjustified belief, regardless of truth value. So the good comedian in this scheme is delusional because they have no rational justification for believing in their likeliness of to success, but nonetheless they believe it, and it turns out to be true.

Now for the more contentious extension of this: a believer in God might be called "delusional" in this same sense, even if they happen to be right, because their belief isn't justified.

Visual language versus aesthetic:

I like the term “visual language” over “aesthetic”, because the latter connotes an outsider generalizing and appropriating, whereas the former seems more about recognizing the role graphics and typography play in a particular cultural context.

+ important to note

++

The West coast’s visual language appears dominated by homogenous minimalism in the tech world, and outrageous maximalism everywhere else.

Amanda Hess:

For some students of Buddhism, and critics of capitalism, these applications represent a perversion of a social good in the service of a cult of the self. They call it 'McMindfulness.'

The line between realism and pessimism seems threadbare at times.

reciprocal relationships:

Maybe my personal problem is that I find showing off in a feed to be repulsive — whether it's sharing a success on Linkedin, a selfie on Instagram, a life event on Facebook, etcetera.

Showing off on a personal webpage feels completely fine to me. That's a place where it seems okay in my mind to be openly proud of yourself. And I think that's because there's no necessary reciprocal relationship: when you put something out on your site, sure you're doing it in part so people will see it, but you're not expecting anyone to give you validation in likes and comments. Then when by chance someone reaches out and praises you entirely of their own volition, the validation feels all the more real and special.

On the utilitarianism versus deontology debate:

I wonder if anyone (I'm sure someone) has ever posited that the best action from a utilitarian calculation is to act in accord with deontological principles.

At a glance that doesn't seem far from what one could take Kant to be doing in the Groundwork. The rational justifications for his imperatives are mostly reflexive. Mill, who was somewhere in the utilitarian sphere, seems to be doing something similar in On Liberty: categorically allowing anyone to speak their minds is to the benefit of individuals and society.

So I guess even within the narrow sphere of things I've read, I can tentatively answer my own question in the affirmative.

Intuitively I feel an ethical imperative to attribute where my ideas and assets come from. Or at least, it would definitely feel wrong for me to better my reputation by letting people believe I came up with something that I actually took from elsewhere.

At the same time, I’m a determinist and a materialist, meaning I’m of the opinion that these concepts of responsibility, authorship, credit, etc. are psychological and prone to devolving into self-contradicting nonsense.

There’s a sort of mutually assured destruction relationship between these two images of reality, so the tricky question in my view is how to consolidate them.

If classification is part of the fabric of our intelligible reality, how come we can conceive of a world apart from our classification? Are we really conceiving of it, or is it just a kind of suspension of judgement, like when we discuss 4 dimensionality, or a triangle with 4 sides?

Classification in science:

Are things like the DSM and the question of whether Pluto is a planet rightfully within the domain of science? Or do scientists overstep their bounds when they debate issues of classification?

John Kaag:

Hypocrisy is not a sign that someone's position is bankrupt. It simply means that we don't live up to the ideals that we espouse, and that's probably the case for all of us. If hypocrisy was a reason to dismiss someone, we would have to dismiss everyone.

law of conservation of concepts:

There’s something akin to a law of conservation in creative practice:

Output requires input, and the quality of your output is dependent on the input.

this is how I use this channel:

Agency and ordinary language:

Where do you draw the ‘agency’ line?

If someone does something morally reprehensible out of ignorance, and there’s no way they could have known it was wrong beforehand, are they culpable?

I’m inclined to say no — they couldn’t make an informed decision, so they’re not responsible. But as the determinist that I am, that leads me down a slippery slope; if there’s no such thing as free decisions, we’re not responsible for anything, right?

An ordinary language philosopher might reply that while you could say that, it would only be by stretching the idea of a “decision” beyond its natural use in language. Our moral concepts relate to the way we experience the world as people, not the way the world is generally. Furthermore, within the bounds of our language, we can justifiably call certain actions immoral, certain people culpable. This is all fine to me — it shows that we have a grounds to have moral discussions, by virtue of the fact that we are inescapably human.

But it doesn’t really settle the original question of how to decide when someone is culpable. Even within a language and culture, people reasonably disagree about moral questions. How do you settle such a debate, in absence of a solid logical rule to appeal to?

Elif Shafak:

“Why don’t you want us to look at each other’s drawings?”, Jahan once asked.

“Because you’ll compare. If you think you are better than the others, you’ll be poisoned by hubris. If you think another's better, poisoned by envy. Either way, it is poison.”

you shouldn't let poets lie to you:

What does it take to “get to know” someone?

Is it about their values, beliefs, and practices?

Their likes and dislikes?

The way they typically behave and relate to others?

Their lived experience?

Polemical skepticism:

I’m in a phase of polemical skepticism against a bunch of ideas:

- the concept of identity, or at least the value of contemplating one’s identity

- the notion that design has a function

- the concept of fate

It seems to me that belief in destiny is a form of self-imprisonment.

Life lock-in:

Rather than choosing a particular activity or subject and making it part of your identity, it feels far more productive to pursue specific ideas and letting them take you wherever they lead.

So it’s frustrating that in life we’re constantly confronted with having to make choices about our long-term future based on who we are in the present.

There’s a similar problem in software development that Jaron Lanier calls “lock-in”: programmers make choices when they design a system that they are henceforth beholden to whenever a new feature or function is added. The uninformed decision ends up dictating a lot about the structure of the program, and it’s a pain in the ass to remove that dependency.

Philosophy and design exist because they happen to be things that humans are naturally compelled to do, and because there happens to be an audience for them.

Our work is not grounded in problem-solving or discovering new things about reality or anything else remotely tangible — it's just about feeding our own psychological and cultural interests.

And that shouldn't make us feel bad about what we do! We're human! If we enjoy working on something, no one gets hurt, and we get paid for it, what else matters?

I get that I'm not supposed to use divs as buttons, but it's such a pain to remove default button styling for most browsers.

It seems to me that the question "what is the meaning of life?" is a category error.

Octavia Butler:

Workshops and classes are rented readers — rented audiences — for your work. Learn from the comments, questions, and suggestions of both the teacher and the class.

We have non-breaking spaces; are there non-spacing breaks?

Only slightly joking.

Formulaic interactions:

I have a (petty) dislike of the thing where we share something with others so they can respond in formulaic and superficial ways. Examples:

- Announcing a success on Twitter

- Announcing a hardship on Twitter

- Sharing a photograph of ourselves on Instagram

When we share ostensibly for attention and validation — that is why we do it, what we expect, and what we get. People respond to the sharing with cookie cutter exclamations that have no real content or personal relation to the receiver. It's like giving someone a hallmark card, or feigning enthusiasm when a child shows you their drawing.

It just feels so utterly empty and performative to me. I know people get joy and comfort out of it, but it's somehow infuriating.

*Puts on red hunting hat* "You're all a bunch of phonies!"

I think there is actually a philosophical lead here though. My conviction is there must be some way to differentiate the above from social practices in general (which are almost always formulaic in some way). Maybe it'd be useful to contrast this with saying "bless you" when someone sneezes. "Bless you" is certainly formulaic, and in response to someone doing something. But what is the difference?

- The first that stands out to me is agency; you (generally) don't choose to sneeze, while you generally do choose to share. This makes the former less sinister to me, because it's not like the sneezer has intentionally done this so as to prompt you to give them this response.

- This leads to another difference though: perceived validation. "Bless you" is pretty empty, but it's also unambiguously empty; there's no pretense when I say "bless you" that I have any particular care for you. On the other hand, the sort of sharing I described is in my opinion utterly empty, but we still pretend that there's some kind of warmth and purity to the interaction.

This actually gives 'bless you' the potential more personal and meaningful than responding to someone's share. The sneezer doesn't have any ulterior motives, and there are times when the blesser isn't obligated by civility to say "bless you", so it becomes a random little act of kindness.

It's funny how energizing it is to do a downloads folder deep-clean

I've been feeling pretty burnt out after finals, but going through the folder gives me a chance to look back through scraps and screenshots from past months and remind myself of the projects that inspire me.

Roy Batty death soliloquy, Ridley Scott's *Bladerunner*:

I've seen things you people wouldn't believe. Attack ships on fire off the shoulder of Orion. I watched C-beams glitter in the dark near the Tannhäuser Gate. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain.

Addendum to Category vs quality:

I wonder if this can be related to categories versus tags in ontology.

I usually think of categories like buckets. Something can’t be in two buckets at a single time. Another way to think of them is like key-value pairs. E.g. the key is “taxonomic class” and the value (category) is “mammalia”.

On the other hand, tags are more like circles in a venn diagram. You can be part of multiple. I think qualities are usually thought of like tags: something has the quality of being green, round, smooth, tasty, etc.

But here’s the thing: it seems to me that you can turn any tag into a category. The tag green becomes the value for the key/category color.

And then the other thing that now occurs to me is that you can have tag-categories. Like a category "ingredients" with an array of such ingredients, which are essentially tags.

Category versus quality:

Aristotle, in the Nicomachean Ethics Book I:

“things are called good both in the category of substance, as God and reason, and in quality, e.g. the virtues, and in quantity, e.g. that which is moderate, and in relation, e.g. the useful...”

What’s the difference between category and quality? I don’t see a substantive one. Maybe this relates to a point that Quine makes in his Two Dogmas paper:

“For Aristotle it was essential in men to be rational, accidental to be two-legged.”

And on the other hand

“from the point of view of the doctrine of meaning it makes no sense to say of the actual individual, who is at once a man and a biped, that his rationality is essential and his twoleggedness accidental or vice versa”

On self definition:

I’ve seen some very clever autobiographies where people say they want to define themselves in broader terms than their discipline or field of study. That’s all well and good, but it still presupposes the notion of “defining oneself”, which even as a concept is far too logically and ethically shaky for my taste.

Look, the point is you’re the one who needs a succinct explanation of who I am. I want no part of it.

There’s something really hilarious about being engaged in two disciplines, neither of which have really figured out what they actually are.

On deadline stoicism:

I think the mantra “trust the process” has a useful application to working on a deadline:

In the past I’ve had moments where I’m under so much time pressure that my anxiety makes me less efficient. Paradoxically, I end up missing deadlines because I spent more time being anxious about the deadline than doing the work. On the flip side, when I’m conscious of a deadline but I let myself get immersed in the subject matter, it becomes a lot more likely that I can finish and be satisfied with the result.

And no matter whether I meet all the deadlines or not, the version of me that trusts the process does the best possible work that could be done within the confined period of time. There’s a stoic sensibility in this that really appeals to me.

This potentially gets complicated by the decision you often have to make about whether and when to contact your supervisor about extending the deadline.

Is the logical concept of implicature 'denotation' or 'connotation'?

"the" cube:

The notion in ordinary language philosophy that a prescriptive statement can be rational within the right context (1) is usefully illustrated by the attempt to translate a statement like "the cube" into formal logic:

Bertrand Russell's translation is:

∃x(Cube(x) ∧ ∀y(Cube(y) → x=y))

That translates naturally in English as:

"There exists a cube X, and any object that is a cube must be X."

This should make us suspicious, because when we said "the cube" we weren't explicitly making any claim about the world. We were only referring to an object in it. Yes, it's implied (2) when we say "the cube" that there is only one cube and therefore we can refer to it that way, but this is in no way "contained" in the phrase "the cube". This information is just background, a contextual framework that must be true in order for it to make sense at all when we say "the cube".

1: I'm thinking of Cavell's Must We Mean What We Say and Anscombe's On Brute Facts. 2: "Implied" only in the sense of logical implicature/necessity.

Conceivability and colors:

Sometimes in logic we say something is necessarily true because we can’t even conceive of it being false (e.g., we can’t imagine a triangle whose angles don’t add up to 180deg).

By the same token, it should be impossible to “discover a new color”, because we can’t even imagine colors aside from the ones we already perceive. And yet, one simply needs to watch a video of a color-blind person putting on EnChroma glasses to see this isn’t as concrete as we might at first assume.

It should be made clearer that “metaphysical” and “spiritual”, in their philosophical usage, are very different terms.

There’s a sensation of beauty and elegance that one experiences when working through logical problems — perhaps it’s a result of explicitly stating what one knows implicitly (intuitively) to be true.

Diderot:

When one compares the talents one has with those of a Leibniz, one is tempted to throw away one's books and go die quietly in the dark of some forgotten corner

Natalie Wynn:

People tend to believe things for emotional reasons, and I think that if you can show a person that you’re a human being, that has a bigger effect than any logical argument you can make.

All you ever meant:

It’s a great exercise to consider “all you ever meant” by a word, as opposed to “what it is”.

I would argue that it even has the potential to resolve something like the question of consciousness.

This is closely related to Dennett’s “manifest experience”.

Wanting something doesn’t necessarily mean it has a place in your hierarchy of goods —

It doesn’t always make sense to say “I want this because..,”

Sometimes you just want it because you want it; it’s reflexive.

Whenever I read something poetic, I gravitate between appreciating it for its beauty and despising it for its ambiguity.

Poetic language sometimes has the quality of deceiving us into believing something outright false or simplified beyond recognition.

A related channel I just found: You will continue to interpret vague statements as uniquely meaningful

Daniel Dennett on relating the manifest image to the scientific image:

If we look at the whole world, and all the 'things' in it, we find that the things are extraordinarily various. On the one hand we have atoms and proteins and quarks and the rest, and neurons. But then on the other end of the scale we have colors and dollars and home runs and opportunities and lies and expressions and all sorts of human-level, middle-sized, and very curious things — words themselves! Now what’s the relationship between ‘things’ of that sort and ‘things’ of the scientific sort? How do we relate the manifest image to the scientific image? Well it isn’t easy. Things don’t just mesh. That’s where philosophy has a lot of work to do.”

Scientists often try, and they don’t do a very good job of it. They typically get impatient and say ‘OK, really, there’s no such thing as a dollar — they don’t exist. Colors don’t exist! No, free will doesn’t exist! None of those things! All are atoms in the void.’ Even if there is a sense in which that’s right, there’s another sense in which it’s just obviously wrong. Getting clear about what the relationship is between the pound sterling in your wallet or in your bank account, getting clear about how that fits in the physical realm, is not really the job for economists, and it’s not the job for physicists. It’s the job for philosophers.”

Spatial relationships:

To the best of our current scientific body of knowledge, do all qualitative properties of matter break down into spatial relationships?

I suspect quantum mechanics complicates this; or time generally.

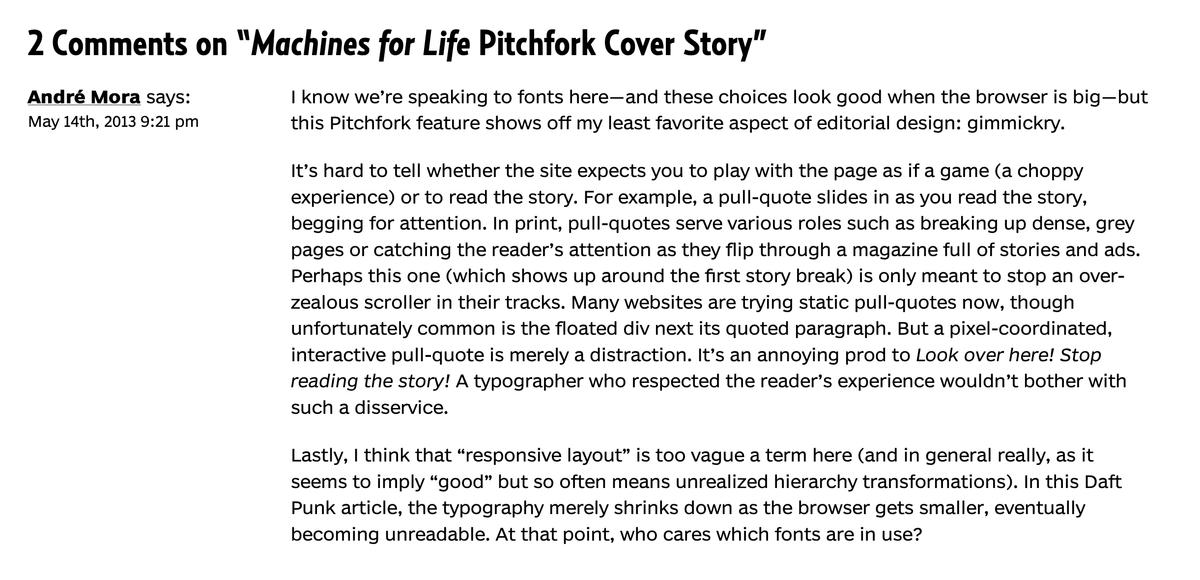

a critique of gimmickry:

Foreign objects:

Reading philosophy from outside of my subfields of interest is like being handed a foreign object and asked to use it with no instruction manual.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but I think it’s a matter of proportion — I’m at a point in my academic life where it’s not profitable anymore for me to spend the majority of my time reading things outside the scholarly areas that I know to be my serious interests.

I lose the time that I would spend becoming good at the things I want to be good at on figuring out things that I don’t have much investment in.

John Ruskin:

I know you feel as if I were trying to take away the honour of your churches. Not so; I am trying to prove to you the honour of your houses and your hills; not that the Church is not sacred — but that the whole Earth IS.”

Reading works of philosophy can sometimes feel like panning for gold

Reading the first couple pages of chapter 12 in Stanley Cavell’s The Claim of Reason makes me feel like an explorer in the very heart of a deep cave after an arduous journey, confronted with a great dragon.

Along the way there have been foreboding claw marks in the wall

I feel this way because he precisely gets at the fundamental question that I have been asking since reading Hume, and Hume only represented the moment that I first acquired a concrete consciousness of it

(the claw marks are wittgenstein)

What is the difference between a theme and a classification? A theme somehow seems more fuzzy

Or maybe a better question is, when are these words respectively used?

Writing with a decisive voice:

It’s always seemed paradoxical to me that students are asked to write from a decisive point of view; about half the time I really don’t feel that I have such a firm opinion about an idea or a text.

But at the same time, I recognize that writing from a decisive perspective forces you to really give voice to and question your own understanding, which perhaps makes your conception more robust than it would otherwise be.

This might be a thread in a future train of thought about the dialogical (ugh) pattern our thought seems to naturally take. Arendt, in the footsteps of Heidegger, conceived of thought as a constant dialogue with oneself. And of course we have the all-importance assigned to dialogue in Plato/Socrates, for whom it was privileged over any form of written expression.

are strict definitions biconditional statements?:

Is a strict definition just a biconditional statement?