On bookshelves and bowers

updated 5/3/2025

Some autumns past, Emily and I attended a lecture by a curmudgeonly Swiss designer, in which he described his experience exhibiting and selling work at art book fairs. Almost in passing, he shared one anecdote in particular that simply struck me, in the way things do when they prompt you to question something that, for all this time, you’ve simply taken for granted; like tugging at a thread that undoes a delicate stitch, such that you lose track of how or if it originally held together.

As he recounted: whenever someone made a purchase at his table, he would ask, “why are you buying this book?”. A straightforward question, albeit a strange one to pose to your patron. The answers, in his telling, varied depending on where he was. In New York (insufferable snobs that we are), people started listing references, explaining their familiarity with the artist, the subject, and so forth. By contrast in Los Angeles, people apparently seemed offended by the question: “what do you mean? I just like it!”.

His point, I gathered, was to praise the latter attitude: the idea of setting aside your prejudices and appreciating (desiring to own?) a book purely on the basis of your first encounter with it, and its formal qualities. Maybe I’ll have something to say about this later. But in the moment, the question jarred me simply because I wasn’t sure how I might answer — why do I purchase the books that I purchase?

To be fair, it’s not that I couldn’t answer in the way that his patrons did, referencing qualities that I enjoy about the specific thing that I was buying. On one level, this type of response is perfectly reasonable. But my sudden feeling was that there should be something underneath this; some explanation for why it’s worth it to buy books in general, which I could then use to decide the merits of any individual purchase.

And before a crowd pursues me with pitchforks, I should clarify that I find tremendous value in books and their contents — only, it’s unclear to me how that value arrives in the form of ownership. When it comes to your wardrobe, for example, ownership confers the benefit of reliable, privileged access to your garments. Each of these garments is something that you use semi-regularly, or if you aren’t using it, the prevailing wisdom is there’s no sense in keeping it around. But books! Books are usually easily and quickly accessible at no charge, through library loans, digital archives, illicit PDFs, and so on. Moreover, we often relate to books in a finite, ephemeral manner: moving from the first page to the last, and then announcing that we’ve “finished”. Once you read all the words to your satisfaction, someone might therefore ask, what further use do you have for the paper on which they're printed?

The first thing I’d say in my defense as a book owner is that this idea of “finishing” books is misconceived; it frames reading as a sort of transmission process, whereby you take in the contents of a book like filling a cup from a pitcher. Maybe this makes some sense when we’re talking about novels, which lose a bit of their entertainment luster after you’ve read them, because you know what’s going to happen. But arguably if you approach reading as anything more than a process of consumption or memorization — when you approach it as an opportunity to learn, to think, to challenge your preconceptions, to aesthetically engage with prose, to explore rich meanings and perspectives — this framing stops being helpful. As Andy Matuschak and Michael Nielsen write in the essay Timeful Texts, “to be transformed by a book, readers must do more than absorb information: they must bathe in the book’s ideas, relate those ideas to experiences in their lives over weeks and months, try on the book’s mental models like a new hat.” I would like to foster active reading processes like the ones they describe, whereby books usually benefit from a long-term, non-linear, repetitive engagement, in the pursuit of deepening one’s understanding and tying together ideas from different texts.

There is also, I think, a reasonable defense to be mounted for the functional role that a book collection can play in the design of personal spaces. By giving it prominence in my apartment and making the books easily accessible, I hope that my shelf can be a way of generally cultivating studiousness and curiosity, and of changing my relationship to reading. Nassim Nicholas Taleb, for example, praises the idea of an “antilibrary” (inspired by Umberto Eco), in which you build a collection full solely of books you haven’t read, such that “the growing number of unread books on the shelves will look at you menacingly”, reminding you of all that you don‘t know and hopefully prompting you to seek knowledge. In a similar vein, Andy Matuschak writes: “Unread digital books and papers live in some folder or app, invisible until I decide that ‘it’s reading time.’ But that confuses cause and effect. When I leave books lying on my coffee table, I’ll naturally notice them at receptive moments, and I’ll decide to start reading based on my reaction to a specific book.” So there’s an idea here of books and bookshelves as research tools, which by way of their physical presence draw your attention and spur you to explore topics and texts of interest.

Even as I make these arguments though, I feel hypocritical using them as the sole justification for my collection. Being honest with myself, I don’t read or look closely at most of the books that I own on a regular basis. My modest bookshelf already has so much material that it outpaces what I could reasonably read and concentrate on for many years to come, considering all the other ways I spend my time, and the fact that I am a slow and fickle reader. It does at times “look at me menacingly,” but I have come to calmly accept that glare. And of those books that I have read and have no intention to return to, I feel no particular desire to get rid of them.

So here I have to wonder if there isn’t something rather shallow about this practice of collecting. I’m reminded of the “coffee table book”, procured for the purpose not of being read and appreciated, but for sitting on the table and projecting sophistication. I’m reminded of the “Zoom bookshelf”, that pandemic phenomenon of home libraries looming in webcam backgrounds to indicate their owners’ literacy. I’m reminded of collections of ages past, the cabinets of curiosities and salon walls, through which European elites conveyed their colonial wealth and worldliness. The collection becomes, in the words of writer Mik Awake, a “pantomime of erudition”: serving to signal its owner’s identity as someone well-read, refined, holding certain beliefs and interests reflected by the contents of their shelves1. And like any other form of self-presentation, it acts recursively: the collector uses their books, wittingly or not, to inform their own sense of self. As Awake puts it, “a feedback loop of conflations grows out of them: reading with one’s personal library, one’s personal library with the owner’s literary ability, one’s literary ability with the extent of one’s reading, and so on, ad absurdum.”

All this conjures a distasteful image of the collector as one who attempts to purchase, through their books, an identity as an intellectual and literary-minded person. But simultaneously, it points to a broader and less cynical idea of identifying with your shelf: the way that a book collection can serve as a partial catalog of one’s interests, memories, and desires. This sentiment pervades much of the other writing I have found on collecting. Awake himself cannot resist comparing standing in front of his shelf to looking at his own reflection: “Shakespeare, an ancient Webster’s I’d inherited from my father, my humanities course books, Hiram’s Red Shirt, my mother’s Amharic book of psalms. It was a mirror of who I was and wanted to be; I was my books, my books were me, and the desire to write books and live through them confused the matter ever more.” In another essay, the author Shuja Haider echoes this experience of coming of age through his own (CD) collection: “We have a quality in common with collectors of rare books, or antique furniture, or baseball cards, or anything at all. It’s the mood of anticipation Benjamin describes [of] a collection awakening in its owner, that of a self coming into being. I put together a collection that I imagined would belong to the person I wanted to become.”

And then of course is the Walter Benjamin passage that Haider is referencing:

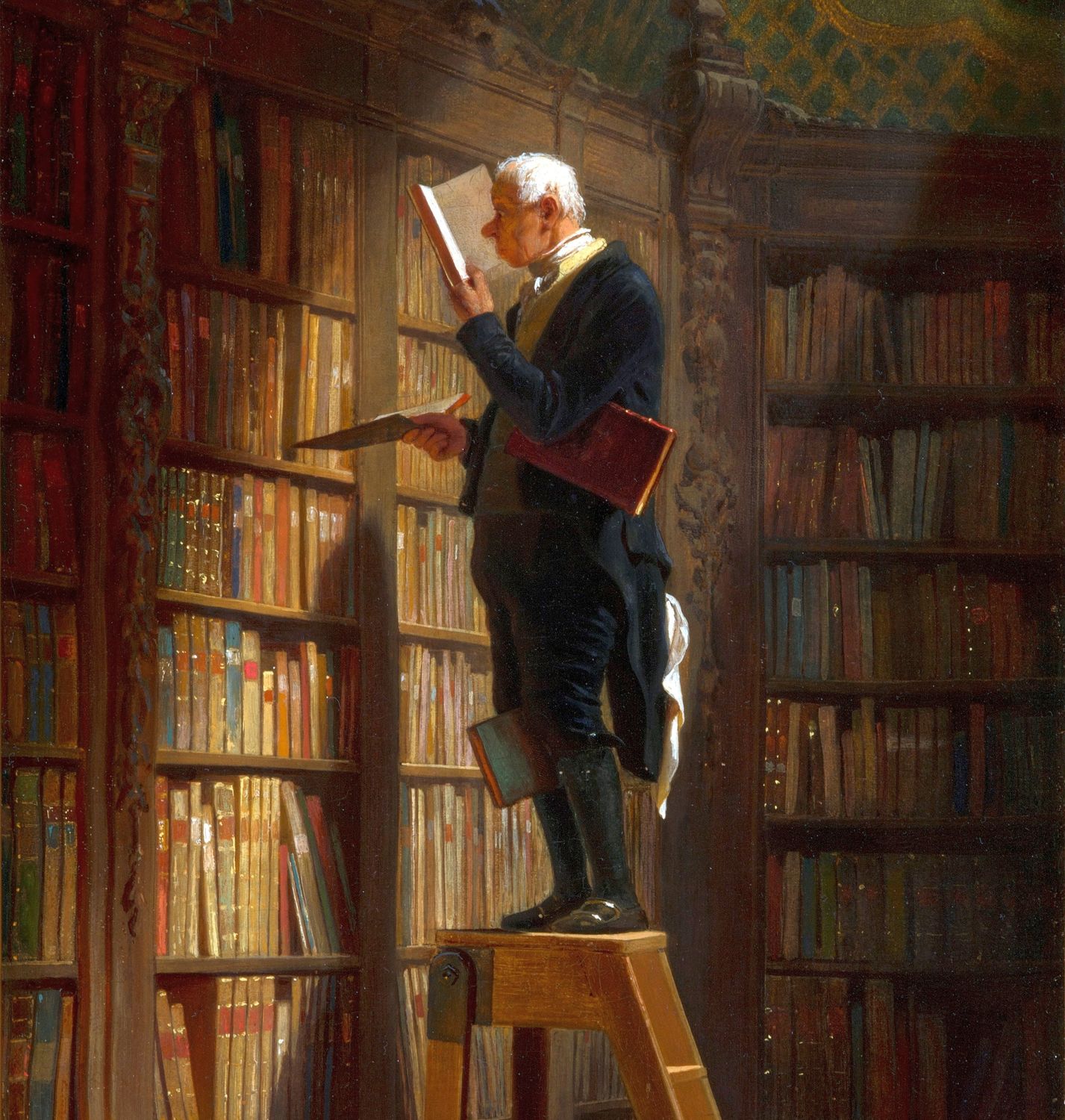

O bliss of the collector, bliss of the man of leisure! Of no one has less been expected, and no one has had a greater sense of well-being than the man who has been able to carry on his disreputable existence in the mask of Spitzweg’s “Bookworm.” For inside him there are spirits, or at least little genii, which have seen to it that for a collector—and I mean a real collector, a collector as he ought to be—ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects. Not that they come alive in him; it is he who lives in them.

A “disreputable existence”, in which “ownership is the most intimate relationship that one can have to objects” — doesn’t that feel a bit icky? Reading each of these authors describe their collections, intermingled with sentimental waxing about each item and how they acquired it, I sensed a degree of shame2. If I might hazard a guess at the source of the discomfort: ownership tends to imply privatizing resources, making them inaccessible to the public and hoarding them for oneself. But as I reflected above, I don’t find this especially applicable in the case of books; my keeping a copy of Spinoza’s Ethics is not reasonably depriving anyone of access in an age where you can get it from any library or download it from Project Gutenberg. And on the flip side of this coin, my acquisition of volumes likely benefits the public good in that it compensates authors and publishers.

Nonetheless I am, by this point, inclined to agree with another view on which these authors converge: my book collection isn’t fundamentally different in its merits from any other type of collection. I won’t be able to justify it purely on the basis of the usefulness of the books; not because they aren’t useful, but because I don’t use them enough for that defense to hold water.

One of the most famed collectors of the natural world is the male bowerbird. To attract a mate, he builds an elaborate nest, surrounding it with hoards of colorful objects scavenged from his environment: flowers, bottle caps, fungi, glass shards, berries, and so forth. He carefully arranges these items, transforming them from natural and artificial detritus into a formal composition, like a collage artist. I feel, as I know many others do3, a strong affinity with him. He is the emblem of my collecting.

Yes, he does it all for the sake of courtship, and that may recall our anxieties about the bookshelf as a social device; but what I identify with in the male bowerbird is this compulsion he seems to feel to make order and beauty out of his surroundings. Lara Palmqvist, in one of my all-time favorite essays, uses his nest as a metaphor for the life of the writer:

In every way, the literary life involves collecting: words and ideas, libraries and anthologies, […] even architectural dictionaries. One of the writer’s essential duties is to gather—to filter and weave fragments, to refract perspectives and form new points of contact.

What this passage and the bowerbird nest reveal is that collecting can be a way of relating to your surroundings: selectively gathering and re-contextualizing objects, putting them in dialogue with one another, and using them to create something that is more than just a composite of its parts.

But again, yes, for the bowerbird, it’s all for the sake of courtship; biologists might warn us not to over-anthropomorphize him, and instead explain his collecting as an instinctive practice calibrated over thousands of years of evolution. However, the fact that this whole procedure evolved at all is, as Ferris Jabr observes for NYT Mag, “an affront to the rules of natural selection”: it is one of those facets of nature which are difficult to explain in functional terms; possibly it emerged completely arbitrarily, or coordinately with some more useful adaptation. Thus out of a kernel of practicality emerges the bower nest, this beautiful and utterly extraneous structure.

The point I’m building towards here is that we may be able to understand our bookshelves in the same way — that is, as extraneous, and maybe, under a certain light, beautiful. The books we collect are occasionally useful as reference points and sources of continuous study — there is our kernel. But what ultimately makes holding onto them worthwhile is the whole range of activity that surrounds collecting. I love, for example, visiting bookstores when I travel; through this act, browsing for additions to my collection becomes an opportunity to explore a city, acquaint myself with new texts and different curatorial approaches, and have enriching conversations with friends and loved ones. Later, standing in front of my shelf, I am struck like Mik Awake and Shuja Haider by the way in which my books reflect the network of relationships and ideas that make up my life. The collection grows, and I'm obliged to treat it like a creative project in its own right: continually re-organizing the items, making connections between temporally or conceptually distant authors, recognizing in the books my past experiences and aspirations for the future.

There is always the potential for a corrupting narcissism and capitalistic excess to seep into book collecting; I can't pretend that my collecting doesn’t ever involve at least a little of these things. Discussing the topic with Patrick a while ago, he made a remark which stuck with me, that we ought to be self-critical collectors. That is: it's incumbent on the collector to use their practice as a way of being more present in the world, rather than receding into one’s belongings. If the value of collecting is in the activities it supports rather than the objects themselves, then we need criteria not only for the kinds of books we acquire, but for the way in which we acquire and make use of them. Without further ado then, here are some principles that I came up with for myself:

-

Privilege independent book-sellers and second-hand acquisition so that you can support authors, ethical businesses, and sustainable practices

-

Privilege in-person buying to online orders, so that collecting can be a conduit for virtuous and social activities like browsing book stores and art book fairs

-

Privilege the serendipity of gifts and chance discoveries, which deepen your relation to places and people

-

In deciding whether to buy a book, privilege context-rich acquisitions, meaning:

-

books that spark memories and have informed your life in important ways

-

books that cultivate areas of interest

-

-

Privilege beautifully designed or formally compelling editions of books4

-

Be open to lending your books and giving them away to others who will appreciate them